Big mistake! Big! Huge! That was the general vibe that Cecilia Gentili was going for in 2016 when she visited her hometown. She was making a lot of money at the time, working the kind of white-collar job that neither she, nor anyone else she grew up with, ever expected her to have, and she wanted to rub all of that unexpected success in their faces — the adults and peers alike who’d scorned her for being too feminine, too dark, too poor, and all around too much for Gálvez, a small city in the northeastern Argentine province of Santa Fe.

And rub it in their faces she did. She paraded her boyfriend around all of the embittered divorcées who’d made her childhood hell. She took others out to dinner — her treat! Because, as she’d remind them with all the mock compassion she could muster, it’s okay, “I know that you’re broke.”

Sitting at her home in Marine Park, Brooklyn, Gentili, now 50 years old, laughs as she recounts her various acts of petty vengeance. “I would be like, ‘Oh, go read my big article that just came out! Oh, wait. You don’t read English. I’m sorry!’”

Though fun at first, her Pretty Woman moment proved to be a hollow victory. “After a while, I realized, why am I doing all this shady shit?” she tells me. We’re sitting on opposing arms of a sprawling L-shaped sectional, enjoying a homemade vegetable-sauce pasta and muddled-mint tequila cocktails while Peter, the aforementioned boyfriend of nearly a decade, watches Survivor upstairs. “There’s much deeper things I want to say.”

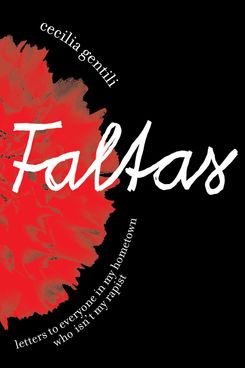

Those deeper things can all be found in her new book, Faltas: Letters to Everyone in My Hometown Who Isn’t My Rapist, released in October. Chronicling the first 17 years of its author’s life, the epistolary memoir is composed of eight letters, each addressed to a different person who radically shaped Gentili’s earliest years through their cruelty, neglect, friendship, conditional affection, and, in the case of her late grandmother, unconditional love. The overarching narrative across those eight letters concerns her experiences with being groomed and raped throughout her childhood and adolescence by an older man she calls Miguel, a since-deceased member of the nationally renowned and locally adored musical group Las Voces de Gálvez. Through her use of the second person, the way we address the recipient when writing letters, Gentili is able to reframe those experiences — as well as her formative clashes with colorism and transphobia — as communal projects rather than isolated incidents, the burden from which only she would otherwise bear.

She opens the book with a blunt, no-punch-pulling letter addressed to her rapist’s daughter, a woman who, these days, Gentili knows only through Facebook posts.

“Saying ‘your father raped me,’ I have had nightmares for many years about having that conversation in person,” Gentili says. “Like, what gives me the right?”

“What does give you the right?” I ask her.

She pauses to think. “Why not? If that’s what I need to do, why do I have to care about her feelings? Why can’t my feelings be more important for once? If she doesn’t like that, if that doesn’t sit well with her, well, it’s okay for once to not give a fucking shit about it as long as it makes me feel better.”

She sips her drink.

Over the past decade, Gentili has risen to become one of the most prominent policy advocates for trans and sex-worker rights in the state of New York. (You might also recognize her from her recurring role as the silicone-pumping, dead-body-disappearing Miss Orlando from FX’s period ballroom drama, Pose.) She has played a leading role in the fight to repeal the “Walking While Trans” ban, the ongoing struggle to decriminalize sex work as a founding member of DecrimNY’s steering committee, the passage of the state’s Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act while serving as the managing director of policy at GMHC, the creation of a state fund for trans-led organizations, and other such causes.

She is also one of the reasons why it’s so easy in New York City, or at least comparatively easier than in most other parts of the country, to get a prescription for HRT.

When Gentili moved to the city in 2003 as an undocumented sex worker, she sourced her estrogen on the black market. “I would get them in the Bronx from this trans girl who would get them in Colombia,” she says. “They had to be Soluna — nothing but Soluna!” The injectable estrogen would make your nipples “blow out so hard that you could not let your T-shirt touch them” for two days after your shot. Aboveboard, you could get a prescription through the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in Chelsea, which had been offering hormones on an informed-consent basis since 1996, but Gentili remembers there being a long waiting list to do so — regularly as long as six months.

In 2009, she was jailed at Rikers on drug-possession charges. She was then removed and detained by Immigrations and Customs Enforcement while the agency began deportation proceedings, only for ICE to let her out with an ankle bracelet in the meantime — essentially because it cost too much money to house her. “They put me with the women, and the women physically assaulted me. They put me with the men, and the men sexually assaulted me. One of the guards told me it’s very expensive to have your own cell,” she says. “Being trans has been, most of the time, a terrible thing in navigating my life, but a couple of times it’s really helped me out.”

Because she wasn’t detained in a facility, Gentili had the time and resources to apply for and receive asylum, thereby ending her potential deportation. (She became a U.S. citizen in September.) She was also able to enter a recovery program for addiction. “In treatment, one of the counselors told me that I have to find something I enjoy as much as that feeling of shooting heroin,” she says, “and that came to be community and working for my community.”

With help and encouragement from Translatina Network founder Cristina Herrera, her peer counselor at the LGBT Community Center, Gentili managed to craft her first résumé, distilling her 20 years of sex work into its most résumé-friendly skills (great at answering phones, very good scheduling capabilities, great at customer service). With that in hand, she applied for a job at the Apicha Community Health Center downtown, where she worked first as an HIV peer navigator and then as its trans-health program coordinator.

Under Gentili’s supervision, the newly launched program, which provides gender-affirming health care on an informed-consent basis, grew from a handful of patients to more than 500 by the time she took a new job as GMHC’s managing director of policy in 2016. “A lot of people were telling their friends, ‘Why are you waiting for hormones at Callen-Lorde? Go to Apicha! They give it to you right away! There’s this crazy woman named Cecilia who fast-tracks everything!’” she laughs. “We had 20, 30, 40 people coming in a week, right? I didn’t have time to write my monthly reports.”

“A lot of people at Apicha started calling me ‘Mom’ or ‘Mother,’” Gentili continues. “I cringe because every time I think about motherhood, I think about my mom, who was a terrible mother.” She bursts out laughing. “When you don’t have a good relationship with your mom, it can be hard to be called ‘Mother.’ So when someone would come into Apicha like, ‘Mooothaaaaa,’ I’d be like, No, girl, I’m not your mother! I’m your case manager! I didn’t think of myself as someone who could handle that responsibility. But I realized that this is a different kind of motherhood. Now, Gia is my daughter. Río is my daughter. Gogo is my daughter. Serena is my daughter.”

A week and a half before our interview, Gentili and I found ourselves at the wedding ceremony of two mutual friends (the transsexual wedding of the century, honestly) held on the outdoor dance floor at the Ridgewood club Nowadays. From the pews, I watched as she strutted down the aisle in her leopard-print Cavalli caftan to give away the bride on the flower-laden altar. “I have this extremely chaotic life where I can’t say no to anything,” says Gentili. “I’ve been saying yes to everything because I never had any opportunities when I was younger. I was queer as a child, trans in my 20s, an addict in my 30s.” The next morning, she jetted off to San Francisco for a business trip on behalf of Trans Equity Consulting, the agency she founded in 2019. After a few days of back-to-back meetings, she hopped a red-eye back to New York to walk in fashion designer Gogo Graham’s SS23 runway show at Mayday Space in Bushwick, where she modeled a pleated, tea-dyed silk-habotai fabric gown and a pearlescent headpiece made from lace and epoxy resin. The following day, she booked it to Jackson Heights to serve as grand marshal of the fifth annual Marcha de las Putas, organized by Colectivo Intercultural Transgrediendo, and then finally, a few days later, she made some time for me.

“When you come out of scarcity, every opportunity feels super-important,” Gentili says. “Some of my friends became lawyers or had families and children or have wealth or a house, and I kind of just survived. That’s productive, right?”

One of her “yes”es in recent years was to Cat Fitzpatrick, author of the forthcoming novel-in-rhyme The Call-Out and Faltas’ eventual editor at LittlePuss Press. Fitzpatrick first encountered Gentili’s work at a reading many years ago. Like most anyone else who’s gone to one of Gentili’s live storytelling performances, like her 2017 one-woman show, The Knife Cuts Both Ways, Fitzpatrick instantly became a fan and began encouraging Gentili to write a book. “She has the most amazing sense of dramatic structure of anyone I’ve ever met,” she tells me over drinks at the Rusty Nail in Ditmas Park.

At first, Gentili struggled to figure out how to translate live storytelling to the page. “The beauty of my stories is that they’re never the same. The meat of the story is the same, but depending on who my public is or what they react to, I might keep pulling at something,” she says. “Telling stories without an audience seemed meaningless to me. I need an audience, but I couldn’t picture who my audience would be because anyone could be reading it.” She had to direct her stories to somebody in order to write them, and that’s when it hit her: letters. They could totally work as letters.

Gentili appreciated Fitzpatrick’s editing style, which the former likened to “a kind of editorial T4T” relationship. Between all the panels and speeches she does for work, Gentili has to do a lot of storytelling for “Gay, Inc.” — that is, the LGBTQ-nonprofit sphere. She finds that world’s narrative expectations limiting at times. “They want the inspiration, like, ‘Oh, poor trans woman living a terrible life! She made it through all that terribleness and succeeded!’” she says. “I’ve been edited a lot as a storyteller to get that inspirational part out of me,” whereas Fitzpatrick loved her penchant for sordid tales of sex, drugs, and Jesus tattoos on throbbing cocks. That’s all going in her next book, Gentili tells me, teasing a follow-up that chronicles her years in Rosario where she met transsexuals, became one herself, and began doing sex work.

Still, with Faltas, she’s not trying to please anybody, not even her editor. She no longer feels that she has something to prove. She just wants to tell the truth.

“When I was younger, I used to work in clubs — not doing drag, more like working the room with charisma,” she tells me on her couch. “I was, like, really talentless. But I was really funny and gorgeous and also had an extreme sense of fashion, so people would just pay me to go to bars and entertain people by talking to them.” That keen ability to read a room later served her well as a storyteller, performing for live audiences of all kinds. “I’ve never told a bad story,” she says. “I’m always able to feel people out and give them what they want, so I have a lot of control.”