Radon is a naturally occurring radioactive gas. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), it is the second leading cause of lung cancer after smoking and is responsible for 21,000 deaths in the United States each year. More and more parents are discovering the need for testing the radon levels in their homes, but high levels of this dangerous gas are also found in schools across the country.

The threat of radon gas in schools

Radon gas is measured in picocuries per liter of air (pCi/L). A reading of 0 pCi/L would be ideal, but trace amounts of radon are unavoidable even with the best ventilation. Outdoors, average radon levels fluctuate between 0.1 and 0.4 pCi/L.

Indoors, radon levels increase because radon gas accumulates within enclosed spaces having insufficient ventilation. The higher the radon level, the higher the health risk. When radon levels reach 4.0 pCi/L, the EPA advises action to lower the level.

A nationwide survey conducted by the EPA estimates that nearly one in five schools has one or more classrooms with radon levels reaching or exceeding 4.0 pCi/L (picocuries per liter). This survey means that more than 70,000 classrooms expose students to high short-term radon levels.

How radon enters a school

How does this harmful radioactive gas enter into so many schools? Radon gas constantly seeps upward through the soil beneath the school. Because air pressure in a building is often lower than outdoor air pressure underneath a building, the building acts like a vacuum and sucks air inside. Radon gas is drawn into tiny cracks where floors meet walls, expansion joints, and small openings around pipes and wires.

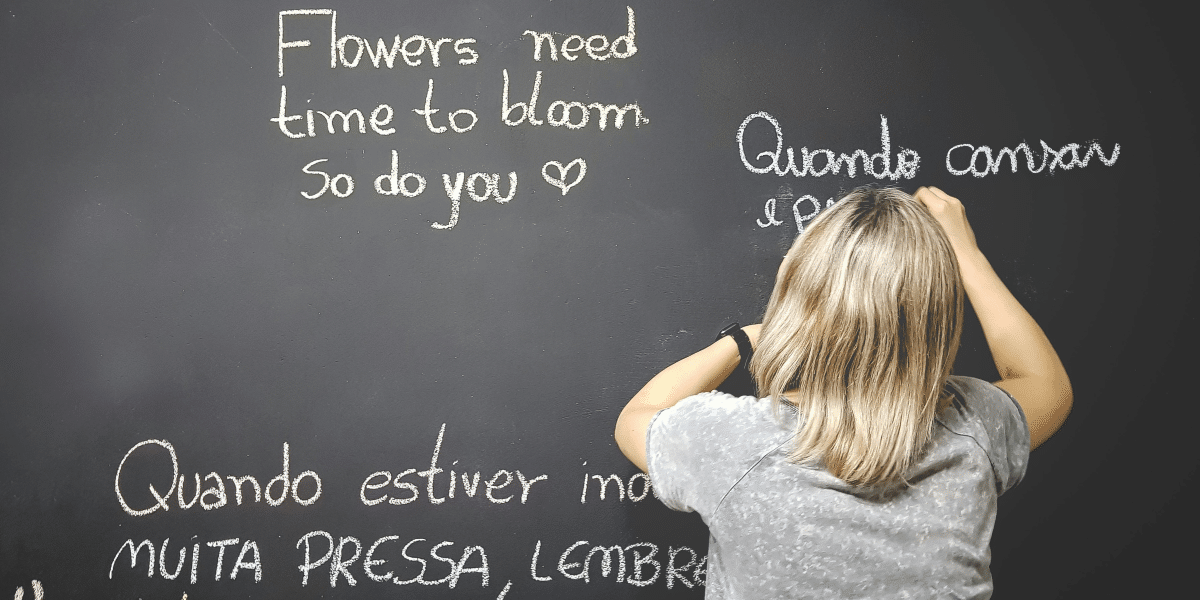

Because radon gas is colorless, tasteless, and odorless, there is no way to detect it without testing. Fortunately, testing is simple to do and inexpensive. Additionally, once testing confirms a problem, there are steps to mitigate and eliminate the gas.

According to a 2005 US Surgeon General Health Advisory, “This threat is completely preventable. Radon can be detected with a simple test and fixed through well-established venting techniques.”

Organizing support for radon testing in schools

Raising awareness among parents, teachers, and school officials to this health risk is essential. The EPA recommends all schools nationwide test for radon. Today, only around 20% of schools in the US have tested for radon. EPA has published guidance that is available free to schools throughout the country.

The first step to set radon testing in motion is raising awareness of the issue with school officials. Once administrators are aware of the need for testing, they can tie their goals for radon testing to their overarching Indoor Air Quality (IAQ), health, and environmental program goals. For more information, the EPA’s Indoor Air Quality Tools for Schools Action Kit offers a handy resource. Radon testing can coordinate with existing IAQ management program activities already implemented by the school.

The next step is to assemble a multidisciplinary team to plan for radon testing and, should it later prove necessary, mitigation. School administrators and facilities managers can connect with radon professionals to gain advice and insight. Other individuals with valuable input include facilities managers, IAQ professionals, air-conditioning technicians, school administrators, staff, and parents.

The importance of communication when testing schools for radon gas

Once testing and any consequent mitigation begin, frequent and transparent communication is key. Administrators should be ready to share the importance of radon testing with families and staff.

They will need to be prepared to communicate those action plans to parents in cases of elevated radon levels. To design the plan, administrators can invite key stakeholders to examine the issue and be part of the solution. Transparency in testing results, mitigation plans, and follow-up testing plans inspire trust and security in the school community.

How to test a school for radon gas

Surveying a school’s floorplans will help determine the number of radon monitors needed for the building and where to place them The EPA’s radon publications for schools contain helpful information to guide the testing process. The EPA suggests testing in all frequently occupied, ground contact rooms.

If high radon levels are detected, the levels can be mitigated quickly by increasing ventilation to the area. As a more long-term solution, a radon professional can survey the site for foundation or slab cracks, poorly sealed penetrations, expansion joints, and other issues that may be responsible for allowing radon into the building.

Because radon levels fluctuate, any kind of effective testing or monitoring must be ongoing. School administrators can use a spreadsheet or electronic work order system to track radon test results and pending actions. In this way, facility maintenance can plan for emerging concerns.

Training the school’s staff members is vital to successful testing and mitigation. By empowering staff with the information they need to test, mitigate, and maintain low radon levels, they will be able to answer questions and concerns from the community.

Ongoing testing and continuous improvements to a school’s radon mitigation plan should be firmly embedded into every school’s safety procedures. Radon is one health risk no child should face, either at home or in school.

The EcoQube by EcoSense is an affordable and easy solution for testing radon levels in schools. This highly-accurate device offers ongoing monitoring and is available on Amazon and the EcoSense website. “Our device offers the speed, accuracy, and useability school administrators need to take action,” says Insoo Park, CEO of Ecosense. “Even simple mitigation strategies such as opening a window or door can effectively lower radon levels in a classroom and improve air quality. These strategies offer time to pursue professional mitigation options.”