The day after Justin Trudeau won re-election, Larry Kitz – a farmer in the western province of Alberta – went online and donated money to a political party with one central goal: separating from Canada. As Kitz tells it, secession was the only cause that matched his growing frustration with the country’s federal government.

“It’s like a bad relationship with someone that’s just draining you all the time,” he said. “On one hand they’ll take the money from you and the other hand they want to knock down [our energy industry]. Eventually you’re gonna have to just call it quits.”

Years of recession and a tepid energy market have helped fuel a growing separatist movement in Alberta, where a fossil fuel industry which once powered a boom is now dragging the economy into bust.

The region – often dubbed the “Texas of Canada” – has some of the world’s largest oil reserves, but a lack of pipelines has made it exceedingly difficult to move the oil to market.

The resulting glut has kept the price of Canadian oil significantly cheaper than other producers, and economists estimate Alberta has shed more than 130,000 energy jobs since 2014. Foreign companies have fled the region.

Anger at the ruling Liberals is palpable. In October’s federal election, Trudeau’s party lost all its five seats in Alberta and Saskatchewan, even though his government had paid billions to help along a controversial pipeline project.

Liberal policies focused on reducing carbon emissions and economic dependence on the oil industry, have only added to opposition in the staunchly Conservative region.

“People feel clobbered. Economic conditions are bad, but at that very point you have governments layering on policies which make the situation worse. That’s why people are directing their anger toward the federal government,” said Amber Ruddy, a political strategist at the conservative lobby group Counsel.

In the face of a looming crisis of national unity, Trudeau last week appointed a new western adviser and moved one of his most senior allies – former foreign minister Chrystia Freeland – to a new position where she will be in charge of negotiations with provincial governments.

But that may not be enough to change opinions in Alberta, where a perception that the federal government is indifferent to the region’s economic pain has given fringe groups a populist rallying cry.

Independence remains a minority cause, but there are signs it is gaining momentum.

At a recent rally with more than 700 attendees in the city of Edmonton, the leader of the newly formed Wexit party told the crowd he intended to submit 543 signatures to Elections Canada for his movement to be designated a federal party.

“There’s this eastern Canadian mentality – a willingness to throw the chains on us,” said party leader Peter Downing, a retired police officer. “In reality, it’s a colonialist mindset and we’ve simply had enough. We’re going to walk away.”

Downing, who has previously run as a candidate for the rightwing Christian Heritage party, says his party is inclusive to all. But there is plentiful evidence of members using racial epithets towards immigrants and Indigenous peoples.

And while Downing and others have framed the frustration sweeping the region as a reaction to recent policies, the grievances of the west have deep roots in the region’s past relationship with the rest of Canada.

In the early 1980s, the prairie provinces rebelled against Justin Trudeau’s father, prime minister Pierre Trudeau, after he proposed exerting greater federal control over the country’s oilfields as a way of hedging against the influence of Opec – at the expense of Alberta’s provincial revenues.

The policy, known as the National Energy Program, was deeply controversial and eroded any Liberal support in the region.

But even further back, westerners saw themselves as bootstrapping settlers whose hard work was frittered away for the benefit of eastern Canada.

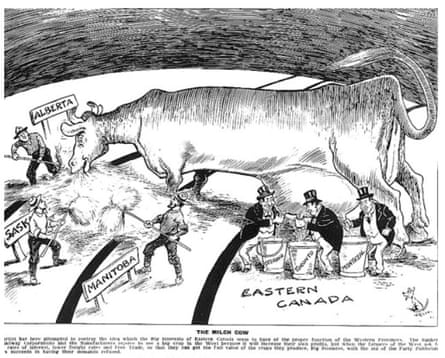

A notorious 1915 cartoon called the “Milch Cow” depicted farmers in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba working hard to feed a cow, while top-hatted bankers directed her milk into buckets labelled “Ottawa”, “Toronto” and “Montreal”.

“People need a myth. They buy into the mythology of the western ‘Pull-up-your- socks, we’re mavericks, we can do it’ story. But there’s no recognition that part of this is just the sheer, amazing luck of living in a place that is not just beautiful, but endowed with natural resources that are beyond belief,” said Aritha Van Herk, an author and English professor at the university of Calgary. “That isn’t virtue. It’s a geological accident.”

Much of the current frustration is linked to an arcane but increasingly controversial financing system called “equalization”, whereby money collected by the federal government from all provinces is redistributed to those with the most need.

Many Albertans, believe that the policy is unfair; Downing characterizes the relationship as one of “expropriation”.

But the popular understanding of equalization in the province – that it is dragging down Alberta’s economy – is plain wrong, said Trevor Tombe, an economist at the University of Calgary.

Despite the recession, incomes in Alberta remain higher than anywhere else in Canada and the province has the highest concentration of people earning more than $100,000 a year.

“Fights over transfers is what Canada is all about. It’s why Canada exists, said Tombe, noting that feuds date back more than 100 years.

The burgeoning separatist cause has found little sympathy in the rest of the country.

Many in Atlantic Canada still remember the economic devastation wrought by a government-enforced closure of the cod industry. Ontario, the most populous province, has seen hundreds thousands of manufacturing jobs disappear in recent years. And in British Columbia, a downturn in the forestry industry has shuttered a number of small towns.

Geography itself would conspire against an independent Alberta, said Van Herk.

“Alberta would be surrounded on four sides. It would be landlocked. It would be surrounded by foreign nations. And in five and a half minutes we’d be annexed by Montana,” she said.

Van Herk sees the secessionist platform as a show of political opportunism by a small minority, but she remains optimistic that a renewed discussion on fairness across the country can mend the growing rift.

“This cleavage is part of the discourse of a really big country – one that needs to talk a lot in order to stay together,” she said. “One of the best parts of Canada is that it stays together as a virtual act of imagination, tied with binder twine and duct tape.”