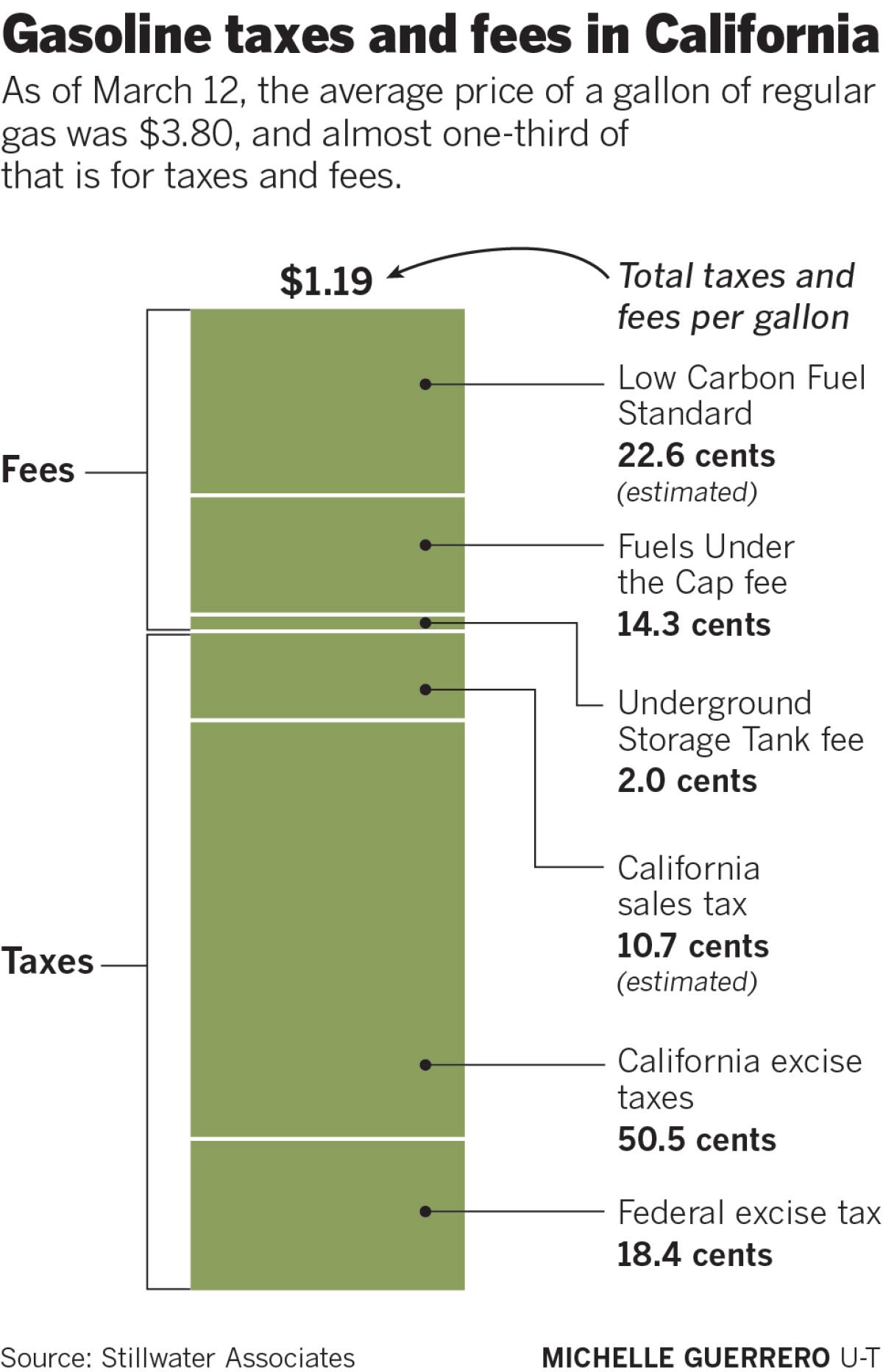

How much are you paying in taxes and fees for gasoline in California?

Irvine-based firm says the amount comes to $1.19 per gallon and some of those costs are associated with state programs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

With gasoline prices on the rise, more drivers are feeling the financial pinch at the pump. After all, California has the highest gas prices in the country.

An analysis from a transportation fuels consulting company in Irvine has determined that Golden State consumers pay $1.19 per gallon, just on taxes and fees.

“I think people will be surprised,” said Leigh Noda, senior associate at Stillwater Associates, the firm that released the analysis. While many California motorists have a pretty good idea about the number of taxes charged on a gallon of gas, Noda said they may not know about other costs associated with state programs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“When you do a Google search for taxes and fees (on gasoline), excise taxes and sales taxes and things like that show up,” Noda said, “What doesn’t show up is the way that climate change fees are levied along the supply chain for fuels.”

Here’s what’s on the tax side of the ledger:

- The federal government charges an excise tax of 18.4 cents per gallon.

- California’s excise taxes on gasoline come to 50.5 cents per gallon. That includes 12.7 cents per gallon from the controversial Senate Bill 1 that became law to improve infrastructure and develop transportation programs across the state.

- Plus, there’s a state sales tax. It can vary by area but the Stillwater analysis estimated the sales tax averages 10.7 cents per gallon.

Put together, Californians pay 79.6 cents per gallon in gas taxes.

Now for the fees Noda says are often overlooked:

- Underground Storage Tank fee of 2 cents per gallon. Established in 1991 following reports of numerous tanks leaking, the fee raises money to clean up underground petroleum storage tanks across the state.

- Fuels Under the Cap fee, which is part of the state’s cap and trade program that requires suppliers of polluting fuels to purchase allowances to offset the emissions that result from burning those fuels. The fee varies depending on the price of the cap and trade allowances and currently comes to 14.3 cents per gallon.

- Low Carbon Fuel Standard, which requires suppliers of fuels with high carbon intensity to purchase credits from makers of fuels with lower carbon, such as ethanol and biodiesel. This fee also varies but using recent prices, Stillwater estimated it at 22.6 cents a gallon.

All told, the fees come to 38.9 cents per gallon.

Add that to the 79.6 cents in taxes, and California drivers pay $1.185 — or rounded to $1.19 — per gallon in taxes and fees.

Using an estimate from the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration that motorists in the state consumed 15.4 billion gallons of gas in 2019, the analysis said the recent increases in the state excise tax plus the Fuels Under the Cap fee and the Low Carbon Fuel Standard equate to $762.3 million in costs at the pump.

Plus, Noda said he expects the Low Carbon Fuel Standard fee to increase in the coming years as California looks to achieve its goals to go to 100 percent carbon-free sources of power by 2045 and eliminate the sale of new gasoline-powered vehicles by 2035.

“The Low Carbon Fuel Standard program is considered to be one of the key programs, like cap and trade, in achieving (those goals),” Noda said, “so they’re going to keep making it more and more stringent.”

But Noda said the Stillwater analysis is not necessarily a call to lower the state’s gas taxes and fees.

“We don’t try to be advocates,” Noda said. “I think that acknowledgment of climate change and trying to mitigate climate change is very important, but I think people should know how much it’s costing. Maybe you’d rather do something differently if you knew that. Perhaps the way to do it is to reduce consumption. There are other choices that people could make.”

The California Air Resources Board points to the fact that the transportation sector is the state’s largest source of greenhouse gas emissions and diesel pollution.

“Our climate and air quality targets can only be achieved by addressing this sector,” CARB spokesman Stanley Young said in an email. “Our policies and programs in the transportation sector are driving the market for clean low carbon fuels, and have displaced more than 16.5 billion gallons of gas and diesel with low-carbon alternative vehicle fuels to date.”

A gasoline mystery

But there’s another potential factor in higher gasoline prices in California.

For years, UC Berkeley professor Severin Borenstein has looked into what he has called a “mystery gasoline surcharge” — an unexplained difference in price, even after all the taxes and fees are taken out of the equation.

Back in 2015, an explosion at an Exxon Mobil refinery in Torrance knocked out about 10 percent of state’s gasoline supply, driving up prices. After normal operations resumed, prices went down somewhat — but Borenstein’s research indicated prices did not completely return to their previous, pre-explosion, levels.

And that residual amount — the mystery surcharge — has never gone away.

Borenstein’s calculations say the differential averaged at least 26 cents per gallon in 2016, 2017 and 2018 and shot up to 44 cents a gallon in 2019.

Borenstein told the Union-Tribune last May he estimated the higher price added up to $27 billion to gasoline consumers. “There is something else going on beyond this that’s holding our prices up so high,” Borenstein said, adding, “We need to keep digging on this.”

Consumer groups have accused oil companies of artificially keeping California prices high. Others have offered other theories for the differential, such as the fact that California has fewer gas stations per driver than other states, leading to less competition between stations and, thus, higher prices.

Last year, the state attorney general’s office filed an antitrust lawsuit in superior court in San Francisco.

Attorneys with the California Department of Justice accuse Dutch energy giant Vitol, along with South Korea-based SK Energy Americas and its trading arm of “a scheme to drive up and manipulate the spot market price for gasoline so that they could realize windfall profits” in 2015 and 2016.

Last month, the court refused to dismiss the case and the companies are expected to answer the complaint later this month.

Gas prices rising fast

All this comes as gas prices have jumped, not just in California but across the country.

After crashing in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the price of crude oil has shot back up. The price of West Texas Intermediate — the benchmark price for domestic crude — stayed in the $40 per gallon range through most of the second half of last year but it is now up to mid-$60 a barrel.

“We’re talking about at least a 50 percent increase in crude oil prices,” Noda said. “And that translates to probably about an increase of about 50 cents” a gallon.

The average price in California for a gallon of regular came to $3.80 on Friday, the highest in the country, according to GasBuddy.com. Hawaii had the second-highest, at $3.49 per gallon. The national average Friday was $2.85.

Fuel analysts say crude prices have gone up for a number of reasons — more people are driving as the economy adjusts to pandemic restrictions and vaccines become more widespread, and the OPEC cartel deciding to keep limits on production, thus tightening global supplies.

Immediately upon taking office, President Joe Biden revoked the cross-border permit for the Keystone XL pipeline that was poised to send about 800,000 barrels of oil a day from Canada to the Texas Gulf Coast and issued a 60-day suspension on new drilling permits and leases on federal land.

Patrick DeHaan, head of petroleum analysis for GasBuddy, said it’s too early to attribute those two moves to the recent run-up in prices.

“Keystone XL was meant to be a pipeline that was built for the future” when additional capacity would be needed, DeHaan said. Plus, although demand is rising, U.S. oil production remains about 3 million barrels per day below pre-pandemic levels.

“Oil companies would be foolish to say, ‘We’ll drill a new well’ instead of reactivating existing wells” until that 3-million-barrel-a-day shortfall is eliminated, DeHaan said. “When things get back to normal — whether it be one, two or three years — then potentially those issues could come to a head ... but none of those are a factor currently.”

Get U-T Business in your inbox on Mondays

Get ready for your week with the week’s top business stories from San Diego and California, in your inbox Monday mornings.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.