UF researchers lead the way in rapidly designing, building low-cost, open-source ventilator

As a University of Florida mechanical engineering student decades ago, Samsun Lampotang, Ph.D., helped respiratory therapist colleagues build a minimal-transport ventilator that became a commercial success. So, when the coronavirus pandemic hit and he heard the desperate international plea for thousands more ventilators, the longtime UF professor of anesthesiology set out to build a prototype using plentiful, cheap components that could be copied from an online diagram and a software repository.

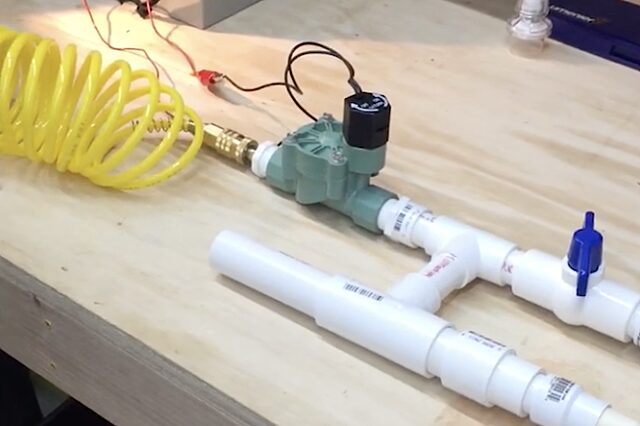

Lampotang dispatched David Lizdas, Ph.D., the lead engineer in his lab, to Home Depot to gather items such as air-tight PVC water pipes and lawn-sprinkler valves. Along with engineering and medical colleagues at UF and — through a burgeoning open-source network — places as far-flung as Canada, India, Ireland, Vietnam and Brazil, they raced to “MacGyver” these items and other pieces, including a microcontroller board and a ham radio DC power supply, into an open-source ventilator they expect to make publicly available in a matter of days.

“The way I looked at it is, if you’re going to run out of ventilators, then we’re not even trying to reproduce the sophisticated ventilators out there,” said Lampotang, the Joachim S. Gravenstein Professor of Anesthesiology in the UF College of Medicine, part of UF Health, and the director of UF’s Center for Safety, Simulation & Advanced Learning Technologies, or CSSALT. “If we run out, you have to decide who gets one and who doesn’t. How do you decide that? The power of our approach is that every well-intentioned volunteer who has access to Home Depot, Ace or Lowe’s or their equivalent worldwide can build one.”

Lampotang, an inventor with 43 patents belonging to UF, will not try to patent the ventilator, he said. Rather, with UF’s approval, he will provide it “open source” for engineers and hobbyists worldwide as the number of critically ill coronavirus victims continues to climb. His team is working on adding safety features to meet regulatory guidelines and then they will run engineering tests to determine safety, accuracy and endurance of the machine, which can be built for as little as $125 to $250.

Gordon Gibby, M.D., said when his friend and former colleague Lampotang contacted him to help, he was a little skeptical. But then Lizdas used the Home Depot materials to assemble a pneumatic circuit, which Lampotang reviewed via FaceTime to confirm that the design concept — similar to the one he helped build decades before — would indeed work. Lizdas, working in his garage, made a video that was uploaded the same night to the website of UF’s department of anesthesiology, where Lampotang and Lizdas are based.

“I saw what they were doing, and realized it was going to work!!!!” Gibby wrote in an email to fellow members of ARRL, the national amateur radio (known as Ham radio) association.

Gibby, a recently retired associate professor of anesthesiology at UF and an electrical engineer, grabbed an Arduino microcontroller board, the kind used to build small robots or for a student to learn to program. Lizdas raced over to his house and dropped off a sprinkler valve in Gibby’s mailbox. Gibby fired up his soldering iron and built a transistor driver that could handle the current supplied by a Ham radio DC power supply.

Eight hours later, Gibby said, two drivers were built, code was created and tested and they had a working ventilator driving a “test lung” metal contraption from an air compressor that served as a simulated oxygen source. They were able to adjust the respiratory rate with the Arduino-based control software. A video of the ventilator working on Gibby’s dining room table was also quickly uploaded. Now, they are working on other key parameters, he said.

The ventilator’s valves will precisely time the flow of compressed oxygen into a patient with lungs weakened by viral pneumonia in order to extend life and allow time for the body to clear the infection.

“It was really easy for me to write the code to prove this thing’s going to work,” Gibby said.

Volunteers who jumped to help included Patrick Tighe, M.D., who prodded Lampotang to act on his idea; the CSSALT team; code developer Marcelo Varanda in Ottawa (motivated to build ventilators for Canada and Brazil); Gibby’s network, including noted software developer Jack Purdum and transceiver maker Ashhar Farhan of India; and Stephanie Lampotang, Lampotang’s daughter, a University of Southern California computer science junior who evacuated to Gainesville with two of her own Arduino boards in her luggage.

Lampotang and others are working with UF Innovate | Tech Licensing and the UF Health legal team to address legal aspects as the design advances and the FDA alters guidance documents for equipment cleared for use solely during the pandemic.

Already, they’ve translated their site https://simulation.health.ufl.edu/technology-development/open-source-ventilator-project/ into French, and a volunteer is translating it into Italian.

“We want to reach the whole world, and The Gator Nation,” Lampotang said. “We have UF graduates from all over the world. There’s already a network of people who can contribute in disseminating the technology if it’s needed in the next few weeks.”

Once the safety features are added, other researchers at UF’s Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering will help run tests to measure and document the safety and durability and whether the accuracy and repeatability meet engineering specifications, Lampotang said.

Nonetheless, he said, his wish is that the ventilator won’t be needed during the coronavirus pandemic.

“When all this comes to pass and the world settles down,” he said, “we hope it will be repurposed for use in underdeveloped countries, so they can build a safe and inexpensive ventilator for themselves.”

If you’re Interested in contributing to the success of these efforts, please consider giving to the COVID-19 Ventilators fund.

About the author