Introduction

On February 1, 2021, the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) took control of the country in a coup d’état.[1] Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in protest.[2] The military regime not only imprisoned political rivals and dissenters,[3] but quickly proceeded to wage war against the people of Myanmar at large with excessive force against protesters,[4] arbitrary arrests of civil servants and other civilians, and indiscriminate attacks on entire communities across the country.[5] The Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), led by civil servants, grew into nationwide strikes across government and private sectors. For their early leadership and broad participation in CDM, health care workers have been targeted by the military with hundreds of arrest warrants for doctors and nurses as well as arrests of health care workers at their jobs and homes.[6] Attacks on health care workers and health care itself has become a prominent feature of the coup d’état.[7] Today, Myanmar is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a health care worker.[8]

Attacks on health care workers and health care itself has become a prominent feature of the coup d’état. Today, Myanmar is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a health care worker.

Hospitals and other health care facilities have been occupied,[9] raided, and shot at by Myanmar security forces;[10] health care workers have been arbitrarily beaten and arrested while providing care;[11] and patients have been arrested while receiving treatment in facilities. Myanmar military have occupied hospitals and used them as military bases, in direct violation of international humanitarian law.[12] Myanmar security forces have raided and taken medical supplies from private clinics and charity organizations focused on providing voluntary medical and social assistance, including those associated with religious organizations,[13] and have warned them not to provide care to civilian protesters.[14] Humanitarian aid, including medical supplies, to displaced populations has been blocked by the Myanmar military.[15] The country was devastated by a disastrous third wave of COVID-19 from July to September 2021.[16] Thousands of people died – mostly at home, without access to any health care facility or provider – due to the collapse of the public health care system and obstruction of health care access.[17]

Hospitals and other health care facilities have been occupied, raided, and shot at by Myanmar security forces; health care workers have been arbitrarily beaten and arrested while providing care; and patients have been arrested while receiving treatment in facilities.

The country’s conflict landscape has changed dramatically with widespread opposition to the coup d’état, including from long-established ethnic armed organizations and newly formed armed forces.[18] The Myanmar military has shelled residential neighborhoods with artillery, burning down homes, cutting off internet access and food supplies, and indiscriminately shooting civilians. This heavy-handed retaliation against opposition to the coup has displaced more than 296,000 women, men, and children since February 1, adding to already significant numbers of internally displaced people across the country and expanding the geographical areas of displacement (e.g. northern Chin state, Magway region, and Sagaing region).[19] Thousands of people have fled across borders to India and Thailand, including almost an entire community of 12,000 people from Thantlang township, Chin state.[20] With indiscriminate attacks on communities and blocking of humanitarian aid by the Myanmar military, humanitarian organizations face safety challenges in accessing conflict areas and displaced populations, including across affected areas that have not seen conflict in recent years or needs on this scale before. [21]

Under international human rights and humanitarian law, states are obligated to ensure effective protection for health care workers at all times, and to provide unencumbered access to emergency health care for all.[22] The people of Myanmar are facing gravely diminished access to routine and emergency health care services, with ongoing and egregious deliberate targeting of health care by the Myanmar military and other armed actors opposing the coup d’état.

Political Context

On February 1, 2021, the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw), led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, contested the results of the November 2020 general elections, where the National League for Democracy, the party led by Aung San Suu Kyi, won by a large margin. The Myanmar military arrested leaders of the newly elected government and declared a state of emergency in which the military would control the country under a caretaker government for at least a year.[23] Widespread peaceful protests quickly erupted throughout the country and military security forces responded to the protests with brutal crackdowns and excessive force, using rubber bullets, live ammunition, tear gas, and water cannons against non-violent demonstrators, and shooting both medical aid volunteers and children.[24]

“Our healthcare workers are working in fear. We are being oppressed, we are forcefully arrested – as are our family members if we cannot be found – and are being prevented from providing proper medical care, resulting in permanent damage to patients and the loss of many lives.”

Mandalay Medical Cover (Partner Statement to UN Human Rights Council)

Newly organized militias formed in opposition to the coup d’état and attacks on communities, mostly notably as part of the People’s Defence Force (PDF) under the National Unity Government (NUG), which was created by a group of elected lawmakers and members of parliament who oppose the coup d’état and military-led State Administration Council (SAC)’s self-declared caretaker government.[25] The NUG has declared its intention to form a Federal Union Army, which would include ethnic armed organizations that have fought against the Myanmar military for decades.[26] In a speech on September 7, the NUG’s acting president called on all citizens to “revolt against the rule of military terrorists” and declared Myanmar to be under a state of emergency until “the resumption of civilian rule in the country.”[27] Some ethnic armed organizations and PDFs have begun to collaborate against the Myanmar military, but the extent of formal alliances and coordinated chains of command that have been or will be developed are uncertain.[28] In the context of escalating armed resistance that has increasingly harmed civilians, the chair of the Kachin Independence Organisation called on civilian resistance groups to stop all attacks on civilians and public facilities, including schools and hospitals.[29]

Methodology

Since February 2021, researchers from the Center for Public Health and Human Rights at Johns Hopkins University, Insecurity Insight, and Physicians for Human Rights, as part of the Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition, have monitored open-source digital materials, including local, national, and international news outlets, social media reports, and communications from partners to identify reports of incidents of violence against health workers, facilities, and transport as well as obstruction of health care in Myanmar. This open-source methodology follows a protocol informed by the Berkley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigations. Incidents are categorized under commonly reported concerns such as: health workers arrested, raids on hospitals, military occupations of hospitals, health workers injured, health workers killed, and incidents impacting COVID-19 response measures. The incidents reported are neither a complete nor a representative list of all incidents. Data collection is ongoing and data may change as more information is made available. Incidents have not undergone verification, but available information is reviewed for evidence of credibility.

Overview of Attacks on Health Care

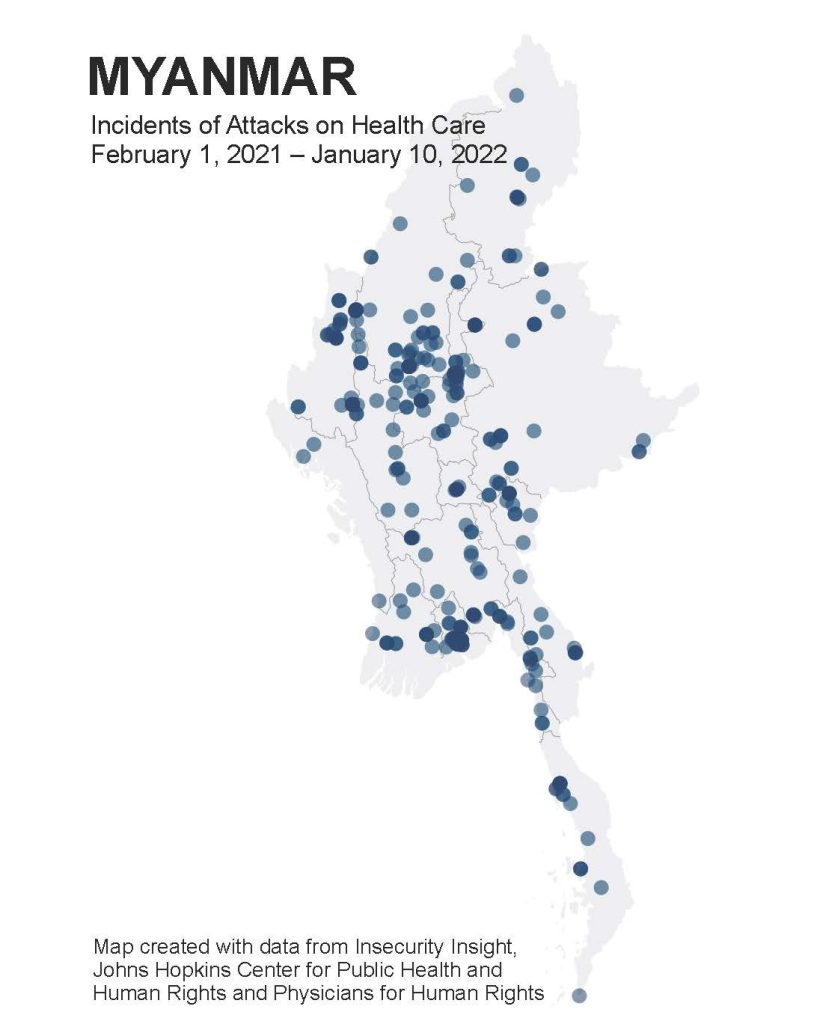

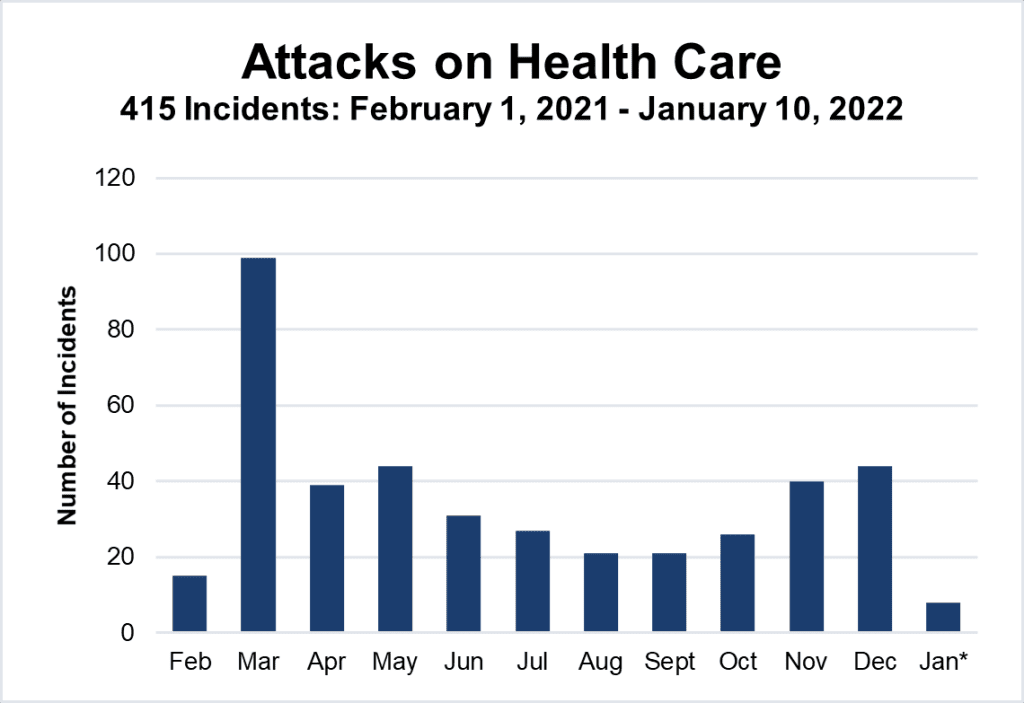

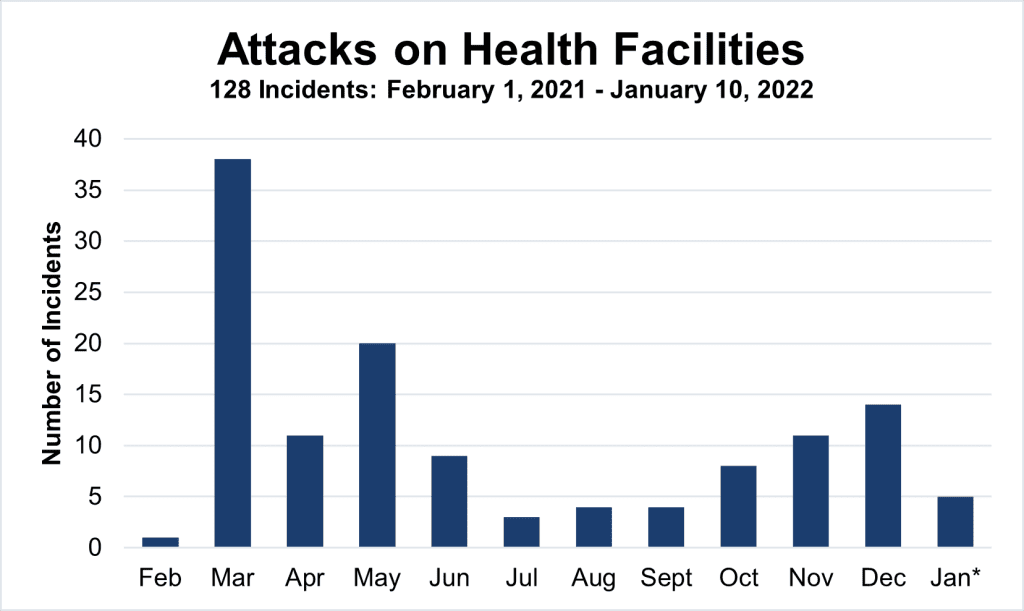

A total of 415 attacks on health care have been documented since the start of the coup d’état on February 1, 2021. Attacks on health care for this report’s analysis include attacks on health care workers, infrastructure, and supplies. While the highest number of incidents were documented in March 2021, there has been a gradual increase in documented incidents from September 2021 through early January 2022. The incidents referred to are available on the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) and are tracked on Insight Insecurity’s global map. Incidents have occurred all over the country, with notable clusters of events in the major urban areas of Mandalay and Yangon; Magway and Sagaing regions; Chin, Kachin, Karen, and Karenni states. Incident trends have evolved alongside the wider events happening throughout the country, such as the nationwide protests, CDM, third wave of COVID-19, and declaration of the people’s defensive war. These trends will be described in more detail below.

A total of 415 attacks on health care have been documented since the start of the coup d’état on February 1, 2021…. It is clear that health care workers are being targeted.

Attacks on Health Care Workers

Health care workers have been under attack since the beginning of the coup d’état. Attacks on health care workers include arbitrary arrests, detentions, and violence committed against all types of health care workers, ranging from doctors and nurses to emergency medics and volunteers.

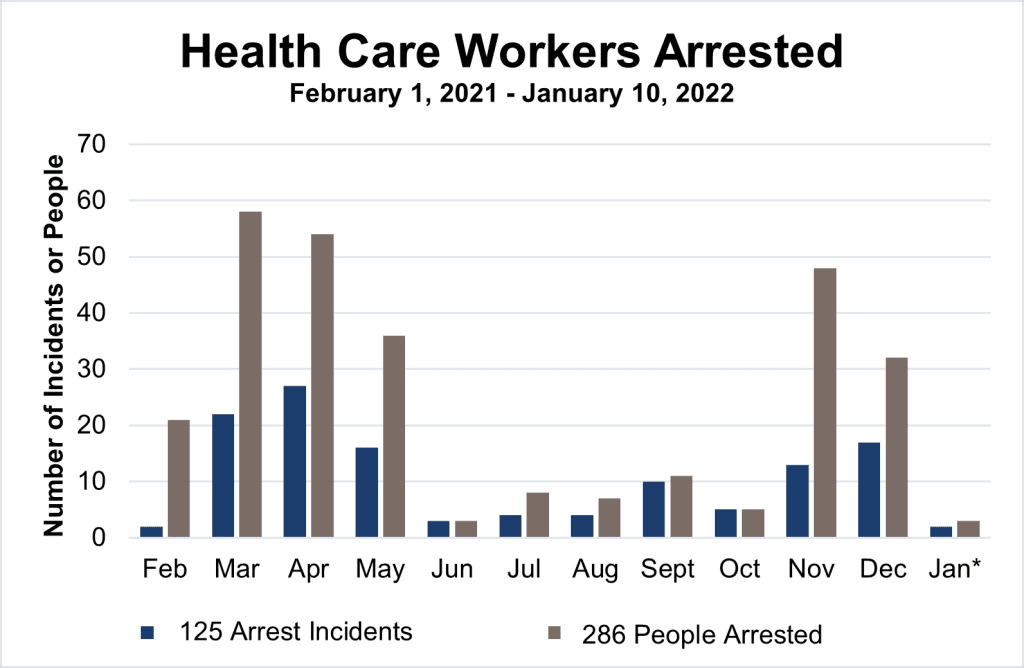

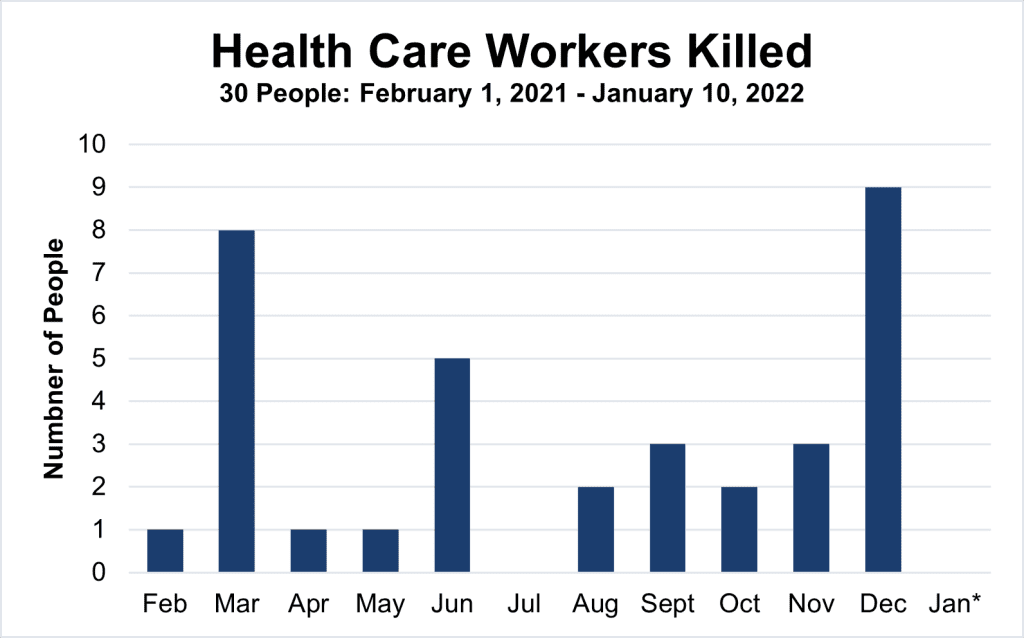

A total of 125 incidents of arrest or detention, with a total number of 286 health care workers affected, have been documented from open sources since February 1, 2021. The difference between the number of arrest or detention incidents and the number of people affected reflects the fact that health care workers are often arrested en masse. According to data gathered by the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners[30], a total of 596 health care workers (out of a total of 1966 people) are actively evading arrest warrants; 132 health care workers have been arrested (50 have since been realized); 82 health care workers remain in detention as of January 10, 2022. At least 25 doctors have been charged with high treason, colluding with an illegal organization, and incitement.[31] Thirty health care workers have been killed since February 1, 2021.

The reports of health care workers arrested in our dataset include arrests that have been made with or without warrants, as well as other incidents of health care workers being detained. It is often difficult to differentiate between arrests and detentions, as routine procedures are often not followed. Additionally, these events are often not reported in the media, as this can reportedly make it more difficult for family members or others to advocate for the release of a person arrested or detained.

Information is more often shared on social media, although posts are sometimes taken down at the request of family members. Arbitrary arrests and detainments of all types and lengths have a harmful impact on health care workers and the provision of health care, so all such reports are included in our dataset.

Over the past twelve months, trends in attacks on health care workers have evolved. Initially, attacks primarily involved Myanmar security forces taking action against health workers participating in nationwide protests, the Civil Disobedience Movement, and the provision of medical care to injured protesters and bystanders.[32] Overtime health care workers believed to have ties to the NUG or PDFs were targeted, including during raids of health facilities and charity organizations accused of aiding injured PDF members or supporters. Attacks by other armed actors on health care workers have emerged, particularly against those who have continued or returned to their civil servant roles and have reportedly pressured staff participating in CDM to return to work, or are believed to be military informants. Media coverage of these events appears to be limited, but such attacks are often reported as committed by unidentified assailants, or to a lesser extent, reported as committed by individuals associated with local PDFs. Publications by the military-led SAC report on these kinds of attacks and sometimes explicitly accuse local PDFs. Identifying who is responsible for these acts of violence is not always possible, but it is clear that health care workers are being targeted.

On January 7, 2022, the deputy director general of the SAC department of public health issued a letter demanding a list of personal details about health care workers affiliated with CDM, including those already dismissed, to be included in a report to the minister’s office.[33] More warrants and arrests of health care workers are expected to follow. Reports are already emerging that arrests are increasingly extending beyond doctors and nurses to include other health care workers who provide basic health care services at local levels across the country.

Security Forces Intimidate and Kill Medics Providing Care to Protesters

On February 27, 2021, Myanmar security forces intimidated the health care workers at a medical base which provided emergency care for protesters in Sanchaung township, Yangon.[34] On March 22, 2021, security forces shot and killed two volunteer medics while they were tending to injured protesters at the Myayee Nanda Housing Estate in Mandalay. On March 28, 2021, security forces shot and killed 20-year-old nursing student Thinzar Hein while she was providing aid to injured protesters in Monywa, Sagaing region.[35]

Police Arrest Celebrated Health Care Humanitarian

On March 12, 2021, police arrested Dr. Than Min Htut, superintendent of Pathein Hospital and recipient of the 2010 “Citizen of Burma Award” for his humanitarian work. When residents across Pathein organized night protests calling for his release, security forces used stun grenades and rubber bullets to quash the protests.[36] Dr. Than Min Htut was among the few government employees who was eventually granted amnesty and released from prison in August 2021.[37]

Violent Home Arrests End with Death in Prison

On June 13, 2021, Dr Maung Maung Nyein Tun and his wife, Dr Swe Zin Oo, were beaten and arrested by the Myanmar military from their home in Maha Aungmyay township, Mandalay under charges of having ties with the NUG. They were charged with high treason under Section 17(1) of the Unlawful Association Act and Section 124 of the Penal Code. Dr. Maung Maung Nyein Tun served the government as a surgeon and a lecturer at University of Medicine, Mandalay. While detained in Obo Prison, he reportedly caught COVID-19 and was transferred to Mandalay General Hospital on July 28, where he died on August 8. He was 45 years old. His wife reportedly also caught COVID-19 in the prison.[38]

Doctors Arrested While Providing Emergency COVID-19 Care

On July 19, 2021, SAC troops called a volunteer medical teleconsultation team under the guise of seeking a home visit for critically ill COVID-19 patients. Three doctors paid a home visit to the presumed patients in South Okkalapa township, where they were arrested. The SAC troops then went to the office of the consultation team and arrested two more doctors.

Nurse Shot by Unidentified Assailants at Private Clinic

A nurse named San Thida was shot dead on November 5, 2021 at around 10:15 a.m. in Parami Clinic in Hlaingthaya township, Yangon region. A witness reported, “The shooter(s) acted as if they were about to purchase medicine, then shot the nurse. The shooter(s) managed to escape after the incident.”[39]

Health Care Workers and Patients are Arrested from Charity Clinic

On November 22, 2021, SAC military and police raided the charity clinic Karuna Dispensary Loikaw Diocese in Loikaw, Karenni state. Eighteen health care workers were arrested, including doctors and nurses. The 48 in-patients being treated at the clinic – seven of them with confirmed COVID-19 cases – were told to relocate to another hospital.[40]

“The SAC has claimed they are trying to arrest Civil Disobedience Movement (‘CDM’) doctors who have shown defiance against the junta and are ‘breaking the law.’ However, many of these violent events involve private doctors who have never worked in government hospitals, volunteer doctors, NGOs and charity clinics that have been filling the gap in healthcare. As such, it is difficult to believe anything other than that healthcare workers as a whole are being deliberately targeted because they are among the first to protest against the coup d’état.”

Myanmar Doctors for Human Rights Network (Partner Statement to UN Human Rights Council)

Township Medical Superintendent Shot in the Head by Unidentified Assailant

On December 14, 2021, at around 7 p.m., Dr Wint Wint Myaing was shot dead while returning back to Kutkai town after a field visit to administer COVID-19 vaccinations. The unidentified perpetrator stopped the doctor’s car, asked her to get out, shot her multiple times in the head, then told the driver and other health staff in the car to leave the scene in the direction they had come from. Dr. Wint Wint Myaing was not a participant in the CDM and had worked for 20 years as the township medical officer of Kutkai Township Hospital.[41]

Charity Organization Ambulance Attacked by Armed Forces

On December 15, 2021, at around 1:30 a.m., an ambulance belonging to a social aid organization was attacked in Falam township, Chin state, allegedly by armed members of the Chinland Defence Force (CDF); the patient, an irrigation department official, was kidnapped and the ambulance driver sustained gunshot wounds. CDF troops later entered the hospital where the driver and other passenger were taken and confiscated their mobile phones.[42]

Attacks on Health Infrastructure and Supplies

Attacks on health care infrastructure and supplies include actions that damage or destroy health care infrastructure and supplies as well as actions that obstruct patients from seeking care or health care workers from providing care in health facilities (including charity run clinics, temporary COVID-19 treatment centers, and emergency medic posts) by violence or threat of violence. These kinds of attacks also include actions that obstruct the safe transport of patients or medical supplies as well as the raiding of medical supplies by violence or threat of violence.

Health facilities have been occupied, raided, and shot at over the past year. During the nationwide protests, Myanmar security forces were stationed at public health facilities to wait for injured protesters seeking medical care in order to arrest them.[43] Security forces also raided private hospitals to find and arrest health care workers participating in CDM as well as protesters receiving treatment.[44] Security forces have occupied hospitals in urban areas before major protests[45] and have used health facilities in remote areas as shelter. They have taken supplies, damaged health facilities with indiscriminate shooting, and arrested health care workers, forcing patients to seek care elsewhere. Ambulances have also been used by Myanmar military for transport of forces and attacks on civilians.[46] These incidents have disrupted the delivery of medical services, hindered access to medical care and the ability of people to seek health care services without fear.

Patients Forced Out of Public Hospital

On March 12, 2021, armed security forces forcibly evacuated all hospitalized patients (approximately 30 people) in Hakha Township Hospital and ordered all hospital staff affiliated with the CDM out of the hospital. At least one patient is reported to have died after being forcibly removed.[47]

Charity Group Offering COVID-19 Treatment Raided and Staff Arrested

On July 19, 2021 in North Dagon township, Yangon, armed SAC forces raided the offices of a charity group offering COVID-19 treatment and arrested two physicians. They also seized oxygen tanks, medication, and personal protective equipment.[48]

Security Forces Deny Patients in Ambulance Entry to Hospital at Gunpoint

On July 17, 2021, Myanmar military forces occupying North Okkalapa Hospital in Yangon city forcibly turned back at gunpoint an ambulance carrying COVID-19 patients.[49]

Public Hospital Attacked by Unidentified Assailants

On September 23, 2021, at around 6:30 p.m., unidentified perpetrators set off bomb at Lone Khin Hospital, a public hospital in Lone Khin village, Hpakan township, Kachin state. This followed an earlier bomb blast on September 5 at the same hospital. The hospital had not been used for routine medical services since March 2021, but was being used as a site for COVID-19 vaccinations. No injuries or causalities were reported.[50]

Station Hospital Occupied and Medical Equipment Stolen

On November 16, 2021, at around 4 p.m., Border Guard Forces (an armed force under the command of the Myanmar military) raided a station hospital in Pa-Lun-Taung village, Hpa-An township, Hpa-An district, Karen state. Windows were broken, the building was occupied, and the public was threatened not to enter the compound. Medicines and hospital equipment were stolen.[51]

“In March, the Myanmar military took control of the majority of public hospitals, endeavoring to reopen them using military personnel. However, the stationing of troops inside the hospital compounds caused many civilians to fear seeking care there.”

Mandalay Medical Cover (Partner Statement to UN Human Rights Council)

Health Facilities Destroyed

Myanmar military attacks continue to damage health facilities, including the Kathea Village Sub Rural Health Centre[52] and the Pekon Rehabilitation Center, both in Pekon township, Shan state.[53]

Human Rights and Health Crisis in Myanmar

Timeline: February 2021 – February 2022

The Myanmar military declares it will take charge of the country for the next year, jailing State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Myint, and scores of other elected senior officials. Nationwide protests start, with hundreds of thousands of people participating in peaceful demonstrations.

Health care workers and other civil servants across the country launch the national CDM.

The Myanmar military begins using excessive force against protesters, including water cannons, rubber bullets, and live rounds. Security forces beat, arrest, and kill health care workers while they are providing care to protesters.

Changes to Penal Code 505A enable the military to bring criminal charges against a wide range of people deemed to challenge their authority.

Myanmar security forces raid homes without warrants and arrest health care workers and other civil servants associated with the CDM.

At least 114 people are killed on Myanmar’s Armed Forces Day (March 27) in the bloodiest crackdown against protesters to date, which includes attacks against health workers, indiscriminate firing into crowds of protesters, and extrajudicial killings. Political opposition to the coup d’état is galvanized with the formation of the NUG.

Myanmar security forces go through residential areas after curfew hours, shooting randomly, intimidating residents, and making targeted arrests.

The Myanmar military instigates widespread raids and occupations of public hospitals; patients with gunshot wounds are denied care.

Myanmar security forces raid and open fire on private hospitals and clinics.

Excessive use of force against protesters continues, with the Myanmar military killing more than 80 protesters in Bago town and blocking ambulances from reaching the wounded. Waves of warrants, arrests, and attacks on health care workers continue.

The Myanmar military-led SAC announces that all health workers who have been charged will be disbarred from medical practice and international travel.

The licenses of several private health facilities are revoked for alleged ties to health care workers participating in the CDM.

Myanmar security forces continue raiding private hospitals and charities.

The NUG announces the formation of the PDF to protect the population from violence instigated by the Myanmar military; it announces its intention to form a Federal Union Army, which will include ethnic armed organizations that have fought against the Myanmar military for decades.

Evidence surfaces that the Myanmar military is returning to family members the mutilated corpses of tortured detainees to instill terror.

Nurses are added to the Penal Code 505a warrant list for the first time.

Public hospitals are the target of bombings by unidentified perpetrators, which injure Myanmar security forces and staff not associated with the CDM.

Health care workers with warrants issued against them continue to live in fear of arrest, with many still in hiding.

Dr. Htar Htar Lin, former director and program manager of Myanmar’s Expanded Program on Immunization, who led the country’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout, is arrested with her husband and seven-year-old son.

The Myanmar military-led SAC suspends operations of the humanitarian organization Médecins Sans Frontières’ (MSF) in Dawei, Tanintharyi region, affecting more than 2,000 HIV and tuberculosis patients.

Myanmar descends into a deadly third wave of COVID-19, with crematoriums in Yangon reportedly handling more than 1,000 extra bodies per day. Long queues for oxygen cylinders and essential medicines are reported across the country.

Myanmar military forces open fire on crowds waiting to refill oxygen tanks.

The Myanmar military-led SAC’s Deputy Minister of Information, Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun, confirms military authorities are restricting oxygen, providing the rationale of “unnecessary use of oxygen supplies”.

Reports indicate that nearly 50 prisoners held in Myanmar’s Insein prison are infected with COVID-19, but are being denied adequate medical treatment.

The third wave of COVID-19 continues, with positive test rates exceeding 35 percent and reports suggesting some of the highest COVID-19 death rates in the world. Senior General Min Aung Hlaing announces the formation of a caretaker government and appoints himself prime minister.

A small number of imprisoned health care workers and other civil servants who joined CDM are released, but according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, a total of 5,474 people, including 70 health care workers, remain in detention and 1,964 are still in hiding to evade arrest warrants.

COVID-19 positivity test rates start to decline. The NUG’s interim president, Duwa Lashi La, declares a defensive war against the Myanmar military. Myanmar’s currency loses more than 60 percent of its value in one month, driving up food and fuel prices in the country’s failing economy.

Thousands of villagers in Sagaing region flee amid fears of Myanmar military raids.

The Karen National Union and Karen National Liberation Army seize Myanmar military bases in Bago region and the Myanmar military retaliates with airstrikes against villages in the area.

More than 3,000 people from villages in Gangaw township, Magway region are displaced by Myanmar military raids in an attempt to crush anti-coup resistance movements.

The military-led SAC authorities close the cases of 4,320 people facing charges and release 1,316 people imprisoned for taking part in anti-coup protests since February, but rearrest at least 110 people again the next day. Arrests of health care workers and raids of their homes continue.

Myanmar military raid and burn more than 200 homes in Thantlang town, Chin state.

Myanmar military attack and damage health facilities, such as the Kathea Village Sub Rural Health Centre and the Pekon Rehabilitation Center, both in Pekon township, Shan state.

Clashes between the Myanmar military and local PDF forces escalate in Chin state, Magway region and Sagaing region, with the Myanmar military sending reinforcements to these areas and carrying out airstrikes.

Thantlang town in Chin state suffers numerous instances of burning, which destroy homes, churches, and an NGO office.

The Kachin Independence Army takes control of three Myanmar military outposts in Hpakant township, Kachin state and the Myanmar military retaliates with airstrikes.

Myanmar military forces raid a charity clinic and arrest medical staff operating in a church in Loikaw town, Karenni state.

Myanmar military clashes with ethnic armed organizations and PDFs continue, with multiple instances of civilians being killed or displaced by Myanmar military airstrikes and heavy artillery attacks across multiple states and regions of the country.

The remains of at least 35 charred bodies, including four children and two staff members of the NGO Save the Children, are found near the village of Moso in Karenni state early Christmas morning. The Karenni Nationalities Defence Force accuse the Myanmar military troops who were present in the area of committing the crime.

The military-led SAC authorities focus investigations and arrests on CDM nurses working in private hospitals, especially in Yangon and Mandalay regions.

Multiple incidents of attacks on ambulances by Myanmar military or PDFs are reported.

The UN Security Council condemns the Christmas Eve killings in Karenni state, stressing the need to ensure accountability and calling for the immediate cessation of all violence, respect for human rights, and safety of civilians. At least one third of officer-level civil servant health care workers are estimated to still be participating in the CDM.

The military-led SAC permanent secretaries meet on January 3, 2022 and discuss pressuring civil servants participating in the CDM to come back to work by arresting them, especially those from the health, education, and rail sectors.

Deputy director general of the department of public health issues a letter demanding a list of personal details about health care workers affiliated with CDM. More warrants and arrests of health care workers are expected to follow.

The chair of the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO) in his New Year’s address exhorted civilian resistance groups to stop all attacks on civilians and public facilities, including schools and hospitals.

Attacks on Health Care Exacerbate Disastrous Third Wave of COVID-19

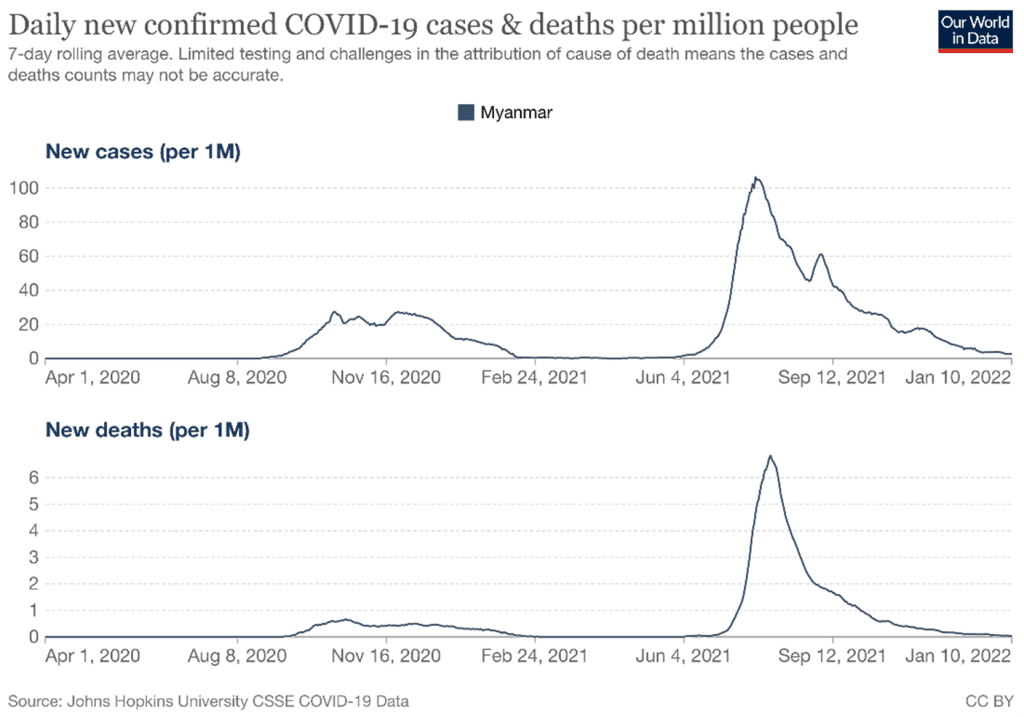

The military coup d’état has exacerbated the dire COVID-19 situation in Myanmar by disrupting vaccination rollout and hospital capacity improvement, destroying public trust and support for the implementation of prevention measures, and obstructing public access to lifesaving medical supplies and health facilities. Local media reports documented the devastating impacts of the COVID-19 “third-wave” (July – September 2021) with an unprecedented surge in deaths, which overwhelmed crematoriums and cemeteries.[54] While local officials were able to respond to the first and second waves of COVID-19 with the strong support of the public, lack of public trust and support contributed to the military’s flailing response to the third wave.[55]

Myanmar survived the first wave of COVID-19 with relatively little harm, reporting 374 cases and six deaths from late March to early August 2020.[56] Cases did not begin to rise significantly until September 2020, reaching a total of 119,788 confirmed cases and 2,532 deaths by late December 2020, according to government data.[57] While the SAC-controlled Ministry of Health data is assumed to be under reporting total confirmed cases and deaths due to lack of adequate testing and surveillance, there has still been a dramatic increase in reported cases and deaths since February 1, 2021. By January 2022, the total number of confirmed cases stood at more than 500,000 and the total number of deaths at more than 19,000.[58] In part, these figures reflect the military’s obstruction and/or termination of COVID-19 prevention and control measures since the start of the coup d’état.

In late January 2021, Myanmar became one of the first southeast Asian nations to begin vaccinating its population. On January 22, it received 1.5 million doses of Covishield/AstraZeneca from India, which it began administering to health personnel, front line workers, government officials, and parliamentarians.[59] The government ordered an additional 30 million doses from the Serum Institute of India and planned to begin vaccinating the public on February 5, starting with people at least 65 years of age.[60] The Myanmar Ministry of Health and Sports was also in the process of improving hospital services across the country for treatment of COVID-19 with significant support from the Asian Development Bank, World Bank, and other major donors in the health sector.[61] These efforts were largely halted by the start of the coup d’état on February 1.

Since then, vaccines have been delayed from arriving in country and have not been distributed according to previous plans to prioritize vulnerable groups. Instability resulting from the coup delayed receipt of the second shipment of vaccines from India in February 2021.[62]The Myanmar military commandeered the meager supply that was already in the country and distributed them to soldiers and military affiliates.[63] When and where vaccines were distributed to civilians, there was widespread hesitation, wherein people who were involved in the protests or had expressed anti-military views were fearful of military persecution at the point of vaccination delivery. Myanmar was subsequently slated to receive 27 million doses through the GAVI Alliance’s (formerly the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation) COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (abbreviated as COVAX) program, with the first 5.5 million doses scheduled to arrive in March 2021. However, the military’s failure to demonstrate capacity to distribute vaccines led to COVAX delaying its delivery indefinitely.[64]

It must also be acknowledged that the National Unity Government (NUG), despite several attempts at engaging the WHO and COVAX for parallel vaccine procurement, was frequently blocked due to its status as an unrecognized governing body. This was a crucial misstep in health diplomacy, as the NUG at the time was predominantly based in the so-called “liberated areas” along Myanmar’s borders, and could have distributed critical vaccines to ethnic populations through cross-border mechanisms in collaboration with Myanmar’s many highly capable ethnic health organizations. Appeals to ASEAN and the UN to coordinate a “patchwork” system of vaccine distribution to address gaps in vaccine coverage across Myanmar were largely unsuccessful.

Incidents of the military restricting access to lifesaving medical supplies, raiding charity organizations providing supplies and treatment, and blocking access to public facilities emerge as common themes during the COVID-19 third wave timeframe. Multiple reports indicated that Myanmar military appropriated private oxygen plants in Yangon and began requiring citizens to apply for oxygen at SAC offices.[65] Similar actions were taken in other parts of the country. On July 25, 2021, the military seized an oxygen production facility in Hpakant township, Kachin state and ordered the facility to only refuel oxygen tanks provided by the military. At the time of the seizure, this facility was the only facility capable of refilling tanks in Hpakant township and more than 70 patients being treated for COVID-19 required oxygen.[66] On July 31, 2021, the SAC troops told some 1,000 civilians queuing for medicines to treat of COVID-19 at Shwe Ohh Pharmacy to go home.[67]These attacks on health care service delivery limited access to lifesaving medical supplies and treatment even during the height of a COVID-19 third wave, thus contributing to the high rates of mortality reported.

Final allocation of vaccines through COVAX is contingent on whether they can be distributed at the required speed and scale in a neutral and impartial manner, irrespective of ethnicity, gender, socio-economic status, or political affiliation. Respect for protection of health care workers and service delivery by all armed actors will be essential to make equitable and impartial delivery of COVID-19 vaccines possible. In November 2021, COVAX committed to delivering millions of Johnson & Johnson Covid-19 vaccine doses in December to the border of Thailand and Myanmar under the COVAX humanitarian buffer, which was established to make vaccines available to people living in humanitarian emergencies due to conflict. This represents a significant step for people living in southeast border areas of the country, but much wider efforts will be needed to deliver vaccines to all who need them.

Conclusion

The impacts on the people of Myanmar of the military coup d’état and attacks on health care over this past year are incalculable and will continue to have implications for many years to come – especially as these attacks continue unabated.

Private and ethnic health facilities have experienced higher care-seeking demands, given the limited functionality of government facilities, the reluctance of many to seek services there, and the defection of government civil service health workers participating in the Civil Disobedience Movement, who are now providing health services outside of the context of government health care system.[68] Intensified and expanded conflict, along with indiscriminate attacks on communities, have forced more health workers to resort to secret, mobile approaches to providing health care, similar to those practiced by ethnic and community-based health organizations throughout decades of conflict in border areas.[69] The poorest and those living in conflict-affected situations struggle to access any health care at all and indications of foregone care are increasing, including for routine and non-urgent chronic conditions. Population-level increases in morbidity and mortality are expected with the limited level of routine immunization services and other essential health care services available, thus contributing to an ever-increasing health crisis in the country.

In addition to the direct impacts of attacks on health care, which prevent people from accessing lifesaving health interventions and seeking care without fear, the wider implications of the coup d’état are having a grave impact on health and well-being. The World Bank predicts an annual economic contraction in Myanmar of up to 18 percent for this year and a recent United Nations Development Programme analysis has warned that half of the country’s population could be living in poverty by early 2022.[70] More than 60 percent of households have reported that their health care access has worsened since the start of the coup and a third of households have reported reducing food consumption.[71] The Global Humanitarian Overview has estimated that humanitarian assistance financing requirements have more than doubled since 2021 (from 276.5 to 826 million USD), reflecting the need for wider response plans as well as the challenges of inflation and increased costs of service delivery.[72]Given the trajectory of events at this time, including escalating conflict, increasing numbers of internally displaced people and refugees, and the effective collapse of the public health care system, there is no end in sight to this human rights and health crisis for the people of Myanmar.

“We are determined to continue working until medical personnel can provide required medical care to wounded protesters, the sick, and the injured, freely in each and every corner of Myanmar.”

Myanmar Doctors for Human Rights Network (Partner Statement to UN Human Rights Council)

Recommendations

Health care workers have the obligation and right to treat those in need – regardless of politics, race, or religion – under all circumstances of peace and conflict. Attacks on health care workers violate human rights and are grave breaches of international law. Members of the international community have made commitments to carrying out the requirements of UN Security Council Resolution 2286, which strongly condemns attacks on medical personnel in conflict situations.[73] Many states have formally reiterated their commitments to principles of the Geneva Conventions, including through the July 2019 Call for Action to strengthen respect for international humanitarian law and principled humanitarian action, which was signed by more than 50 states.[74]

Protection of health care workers, health care services and humanitarian access to all populations in need must be respected and supported by all actors in Myanmar. International actors should also support the urgent need for COVID-19 vaccines, care and broader humanitarian support to the people of Myanmar through flexible mechanisms that recognize the evolving nature of conflict dynamics and difficulty in reaching all people in need. This should include support for cross-border delivery of humanitarian aid (along borders with China, India and Thailand) to reach those in need who cannot be reached otherwise.

To the State Administration Council and Tatmadaw:

- Adhere to the provisions of international humanitarian and human rights law regarding respect for and the protection of health services and the wounded and sick, and regarding the ability of health workers to adhere to their ethical responsibilities of providing impartial care to all in need; and

- Cease the targeting of health care workers with warrants and arrests for participating in the Civil Disobedience Movement and peaceful protests or for their provision of health care; immediately release those arbitrarily detained.

- Provide the United Nations, national and international aid organizations safe, sustained and unfettered access to all areas with internally displaced population in Myanmar.

- Cooperate with COVAX to provide equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines to all people in Myanmar, including those to be reached by ethnic and community-based organizations, non-governmental and UN organizations.

To the National Unity Government, Ethnic Armed Organizations and People’s Defence Force:

- Adhere to the provisions of international humanitarian and human rights law regarding respect for and the protection of health care workers, health care services, the wounded and sick as well as the ability of health care workers to fulfill their ethical responsibilities of providing impartial care to all in need.

- Serve and protect Myanmar civilians irrespective of political affiliation, and refrain from fomenting divisions among civilians as it relates to universal matters of health.

- Respect mandates for humanitarian access to all populations in the country.

To the International Community:

- Urge the Tatmadaw and military regime in Myanmar to adhere to the provisions of international humanitarian and human rights law regarding respect for and the protection of health care workers, health care services, the wounded and sick as well as the ability of health care workers to fulfill their ethical responsibilities of providing impartial care to all in need.

- Ensure the full implementation of Security Council Resolution 2286 and adopt measures to enhance the protection of and access to health care in situations of armed conflict as set out in the Secretary-General’s recommendations to the Security Council in 2016.

- Support thorough, impartial, and independent investigations into alleged violations of obligations to respect and protect health care and for the prosecution of the alleged perpetrators of such violations.

- Facilitate the unhindered delivery and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines in areas of armed conflict, as called for in UN Security Council Resolution 2565.

- Support COVAX for the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines to all people in Myanmar and other initiatives to ensure sufficient COVID-19 tests, therapies, and related supplies.

- Increase support to meet growing humanitarian needs, including through cross-border delivery of humanitarian aid (along borders with China, India and Thailand) to reach those in need who cannot be reached otherwise.

“One day without adequate health care is one more day with unnecessary and preventable deaths. The people dying are not just nobodies. They are our country’s future generations, parents of these children, and people that are contributing to the country in their own able ways. As such, it is important for these people to get medical care without any fear and for medical professionals to provide the care whenever and wherever needed…. By effectively and forcibly preventing doctors from providing essential medical care to these people, many lives which could otherwise have been saved are unnecessarily lost.”

Mandalay Medical Cover (Partner Statement to UN Human Rights Council)

Acknowledgments

This report was written by an anonymous author and Lindsey Green, program officer at Physicians for Human Rights (PHR). Data was collected by staff, consultants, and volunteers at the Insecurity Insight, the Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health and Human Rights, and Physicians for Human Rights, including (in alphabetical order by surname) Helen Buck, Brian Elmore, Khin Hnit Oo, Jennifer Leigh, Sandra Mon, Nang Phoo, and Christina Wille.

The research summary was reviewed by PHR staff, including Max Hadler, COVID-19 senior policy expert; Michele Heisler, medical director; Thomas McHale, deputy director of the Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones; Karen Naimer, director of programs; and Michael Payne, deputy director of advocacy. The research summary was also reviewed by Chris Beyrer, director, Center for Public Health and Human Rights at Johns Hopkins University (CPHHR), Sandra Mon, CPHHR senior research program coordinator, and Christina Wille, director of Insecurity Insight.

The research summary was edited and prepared for publication by Claudia Rader, PHR senior communications manager. Hannah Dunphy, PHR digital communications manager, managed the digital presentation.

This document is funded and supported by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) of the UK government through the RIAH project at the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute at the University of Manchester, by the European Commission through the “Ending violence against healthcare in conflict” project, and by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Insecurity Insight, the Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health and Human Rights, and Physicians for Human Rights and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the U.S. government, the European Commission, the FCDO, or Save the Children Federation, Inc.

Endnotes

[1] Russell Goldman, “Myanmar’s Coup, Explained,” The New York Times, January 10, 2022, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/article/myanmar-news-protests-coup.html.

[2] “Anti-Coup Mass Protests Take Place in Cities across Myanmar,” Myanmar NOW, February 7, 2021, https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/anti-coup-mass-protests-take-place-in-cities-across-myanmar.

[3] “Myanmar Military Detained 220 Political Prisoners Since Coup: AAPP,” The Irrawaddy, February 11, 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-military-detained-220-political-prisoners-since-coup-aapp.html.

[4] Physicians for Human Rights, “Myanmar Military Must End Excessive Use of Force against Protestors, Detention of Health Care Workers,” February 18, 2021, https://phr.org/news/myanmar-military-must-end-excessive-use-of-force-against-protestors-detention-of-health-care-workers/.

[5] Joyce Sohyun Lee et al., “How Myanmar’s Military Terrorized Its People with Weapons of War,” Washington Post, August 25, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2021/myanmar-crackdown-military-coup/.

[6] Physicians for Human Rights, “Myanmar Military Must End Excessive Use of Force against Protestors, Detention of Health Care Workers.”

[7] Physicians for Human Rights, “At Least 109 Reported Attacks and Threats to Health Care in Myanmar Over Just Two Months of Military’s Crackdown,” April 23, 2021, https://phr.org/news/at-least-109-reported-attacks-and-threats-to-health-care-in-myanmar-over-just-two-months-of-militarys-crackdown/.

[8] World Health Organization (WHO), “Surveillance System for Attacks on Health Care (SSA),” accessed January 19, 2022, https://extranet.who.int/ssa/Index.aspx; Jonathan Head, “Myanmar Coup: The Doctors and Nurses Defying the Military,” BBC News, January 7, 2022, sec. Asia, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-59649006; Zaw Wai Soe et al., “Myanmar’s Health Leaders Stand against Military Rule,” The Lancet 397, no. 10277 (March 2021): 875, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00457-8.

[9] “Myanmar Junta Occupies Schools, Hospitals And Shutters 5 Media Outlets in Fresh Clampdown,” Radio Free Asia, March 8, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/fresh-clampdown-03082021172256.html.

[10] “Hospitals, Clinics Not Spared Myanmar Regime Forces’ Violence,” The Irrawaddy, April 1, 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/hospitals-clinics-not-spared-myanmar-regime-forces-violence.html.

[11] “Medics, Aid Volunteers Become Latest Targets of Myanmar Junta’s Brutality,” Radio Free Asia, March 4, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/emergency-care-workers-03042021172046.html.

[12] Helen Regan, “Myanmar Military Occupies Hospitals and Universities Ahead of Mass Strike,” CNN, March 8, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/03/08/asia/myanmar-military-hospitals-mass-strike-intl-hnk/index.html.

[13] Esther J, “Loikaw Church Closes Clinic after Military Arrests Medical Staff,” Myanmar NOW, November 24, 2021, https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/loikaw-church-closes-clinic-after-military-arrests-medical-staff.

[14] “Post by AM Htet,” Facebook, March 13, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2956500451341728&set=bc.AbqUF94sQfCDuRPnTzshHG6uca4cTjNjLqxZAdaL2G0sC37zVsnPeztaMetdi00gsyBXHEfNUdAY8t68nks9FLRfMr0m032w4kwzKe9jurHTGSUj-_CLR1f0bMZeCzXtda574rrvrcUYDc4UpA44ZW70PTZD1Nrj2Is6HuUH0N60g3Cjpk7Bwe-D288Lkq4nacJNYrk1WrEcuLm5wuinErli45-L-gcqTDjKpTQ39_4Y45ckGH5BoHuTKnjL39lhsVxA9QI4zNNFsi9Ns9482yeLi_DgmcVQ4DCZGAKnh4nUAw.

[15] Progressive Voice et al., “Nowhere to Run: Deepening Humanitarian Crisis in Myanmar,” September 2021, https://progressivevoicemyanmar.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/No-Where-To-Run-Eng.pdf.

[16] “As Myanmar Regime Mishandles COVID-19, More Than 2,000 People Die in Three Weeks,” The Irrawaddy, July 21, 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/as-myanmar-regime-mishandles-covid-19-more-than-2000-people-die-in-three-weeks.html.

[17] Ian Christopher Rocha et al., “Myanmar’s Coup d’état and Its Impact on COVID-19 Response: A Collapsing Healthcare System in a State of Turmoil,” BMJ Military Health, May 21, 2021, bmjmilitary-2021-001871, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2021-001871; Grace Tsoi and Moe Myint, “Covid and a Coup: The Double Crisis Pushing Myanmar to the Brink,” BBC News, July 29, 2021, sec. Asia, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-57993930; “COVID Cover up: Third Wave Death Toll May Be in Hundreds of Thousands,” Frontier Myanmar, January 14, 2022, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/covid-cover-up-third-wave-death-toll-may-be-in-hundreds-of-thousands/.

[18] International Crisis Group, “Myanmar’s Coup Shakes Up Its Ethnic Conflicts” (International Crisis Group, January 12, 2022).

[19] UNHCR, “Myanmar Emergency – UNHCR Regional Update – 17 December 2021,” December 17, 2021, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/90133.

[20] Sui-Lee Wee, “Thousands Flee Myanmar for India Amid Fears of a Growing Refugee Crisis,” The New York Times, October 19, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/19/world/asia/myanmar-refugees-india.html.

[21] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Written Updates of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar (A/HRC/48/67),” September 16, 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/myanmar/written-updates-office-united-nations-high-commissioner-human-rights-situation-human; Crisis Group Asia, “Taking Aim at the Tatmadaw: The New Armed Resistance to Myanmar’s Coup” (Yangon/Bangkok/Brussels: International Crisis Group, June 28, 2021).

[22] “Medical Neutrality,” Physicians for Human Rights, accessed January 19, 2022, https://phr.org/issues/health-under-attack/medical-neutrality/.

[23] Goldman, “Myanmar’s Coup, Explained.”

[24] “Medics, Aid Volunteers Become Latest Targets of Myanmar Junta’s Brutality”; Nu Nu Lusan, Kyaw Hsan Hlaing, and Emily Fishbein, “Medics Risk Lives to Treat Injured in Myanmar Anti-Coup Protests,” Aljazeera, March 3, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/3/myanmar-medics-risk-lives-to-treat-injured-in-anti-coup-protests; Hannah Beech, “‘She Just Fell Down. And She Died.,’” The New York Times, April 4, 2021, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/04/world/asia/myanmar-coup-deaths-children.html; Physicians for Human Rights, “Myanmar Military Must End Excessive Use of Force against Protestors, Detention of Health Care Workers.”

[25] Mong Palatino, “CDM, NUG, EAO and Other Acronyms of Myanmar’s Anti-Coup Resistance,” Global Voices (blog), June 3, 2021, https://globalvoices.org/2021/06/03/cdm-nug-eao-and-other-acronyms-of-myanmars-anti-coup-resistance/.

[26] Sebastian Strangio, “Can Myanmar’s New ‘People’s Defense Force’ Succeed?,” May 6, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/05/can-myanmars-new-peoples-defense-force-succeed/.

[27] “Myanmar’s Shadow Govt Declares War on Military Regime,” The Irrawaddy, September 7, 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmars-shadow-govt-declares-war-on-military-regime.html.

[28] “NUG Establishes ‘Chain of Command’ in Fight against Regime,” Myanmar NOW, October 28, 2021, https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/nug-establishes-chain-of-command-in-fight-against-regime; International Crisis Group, “Myanmar’s Coup Shakes Up Its Ethnic Conflicts.”

[29] “KIO Chair Warns Resistance Groups About Attacking Civilians,” Kachin News Group (KNG), January 4, 2022, https://kachinnews.com/2022/01/04/kio-chair-warns-resistance-groups-about-attacking-civilians/.

[30] “AAPP | Assistance Association for Political Prisoners,” AAPP | Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, accessed January 20, 2022, https://aappb.org.

[31] “Former Head of Covid-19 Vaccine Rollout Charged with High Treason,” Myanmar NOW, June 16, 2021, https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/former-head-of-covid-19-vaccine-rollout-charged-with-high-treason.

[32] Nu Nu Lusan, Kyaw Hsan Hlaing, and Emily Fishbein, “Medics Risk Lives to Treat Injured in Myanmar Anti-Coup Protests.”

[33] Khit Thit Media, “Khit Thit Media 1/8/22 Facebook Post,” Facebook, January 8, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/khitthitnews/posts/1396506550786687.

[34] The Irrawaddy, “Riot Police Indiscriminately Intimidated and Arrested Bystanders after Cracking down Anti-Military Regime Protesters in Yangon’s Myaynigone on Saturday. (The Irrawaddy) #WhatsHappeningInMyanmar Https://T.Co/PLtfVwOHyZ,” Tweet, Twitter, February 27, 2021, https://twitter.com/IrrawaddyNews/status/1365556852327469057.

[35] Myanmar Now, “Myanmar Now 3/28/21 Facebook Post,” Facebook, March 28, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/MyanmarNowEnglishVersion/posts/2617495638541664.

[36] “Medical Superintendent Charged for Refusing Regime’s Order to Reopen Hospital,” The Irrawaddy, March 14, 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/medical-superintendent-charged-refusing-regimes-order-reopen-hospital.html.

[37] “Myanmar’s Junta Releases Jailed Anti-Coup Activists And Government Employees,” Radio Free Asia, August 2, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/release-08022021165542.html.

[38] “Myanmar Surgeon Arrested by Junta Dies After Contracting COVID-19 in Prison,” The Irrawaddy, August 9, 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-surgeon-arrested-by-junta-dies-after-contracting-covid-19-in-prison.html.

[39] DVB, “လှိုင်သာယာတွင် သူနာပြု ဆရာမ ၁ ဦး ပစ်သတ်ခံရ,” November 5, 2021, http://burmese.dvb.no/archives/498537; Mizzima, “Mizzima – News in Burmese 11/5/21 Facebook Post,” Facebook, November 5, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/MizzimaDaily/posts/4942675189100680.

[40] Myanmar Labour News, “Myanmar Labour News Facebook Post,” Facebook, November 24, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/myanmarlabournews/posts/679018526817208 “စစ်တပ်ဝင်စီးသည့် လွိုင်ကော်ဘုရားကျောင်းဆေးခန်း ပိတ်သိမ်းထားရ“ Myanmar Now, November 23, 2021, https://www.myanmar-now.org/mm/news/9409.

[41] Shan News, “Shan News Facebook Post,” Facebook, December 14, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/shannewsburmese/posts/4656584957767244

“Kutkai Township medical superintendent shot to death,“ Eleven Media Group, December 16, 2021, https://elevenmyanmar.com/news/kutkai-township-medical-superintendent-shot-to-death.

[42] People Media, “People Media Facebook Post”; “Irrigation Dept Official Abducted On Way To Hospital In Falam.”

[43] “Wounded Myanmar Protesters Fear Arrest in Junta Hospitals,” The Straits Times, June 16, 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/wounded-myanmar-protesters-fear-arrest-in-junta-hospitals.

[44] “Myanmar Crisis Heightens with Police Raids and Strike Call,” AP News, April 20, 2021, sec. Shootings, https://apnews.com/article/world-news-social-media-myanmar-media-yangon-aadacc0f45fb4d1a9ef2766fabf82cd6.

[45] Helen Regan, “Myanmar Military Occupies Hospitals and Universities Ahead of Mass Strike.”

[46] “ကနီတွင် စစ်တပ်က လူနာတင်ကားပေါ်မှ ပစ်၊ ရွာသားတစ်ဦးသေ” Myanmar Now, July 31, 2021, https://www.myanmar-now.org/mm/news/7644;

“ဆားတောင် PDF စခန်းကို လူနာတင်ယာဉ်သုံးပြီး စစ်ကောင်စီတပ် ဝင်စီး” Myanmar Now, October 19, 2021, https://www.myanmar-now.org/mm/news/8872.

[47] The Chinland Post, March 12 – Military Deployment at General Hospital in Hakha, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_VeMedQDcpc.

[48] “Junta Lures, Arrests Community Doctors by Posing as Covid-19 Patients,” Myanmar NOW, July 20, 2021, https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/junta-lures-arrests-community-doctors-by-posing-as-covid-19-patients.

[49] DVB, “လှိုင်သာယာတွင် သူနာပြု ဆရာမ ၁ ဦး ပစ်သတ်ခံရ”; May Wong, “Seems #Myanmar #military Has Locked down North Okkalapa General Hospital in Eastern #Yangon & Not Allowing People, Including Paramedics in. Unclear What Reason Is. Hospitals Been Overwhelmed & Authorities Recently Also Requested for Medical Volunteers #WhatsHappeningInMyanmar Https://T.Co/Vp2pvdLTeW,” Tweet, Twitter, July 17, 2021, https://twitter.com/MayWongCNA/status/1416424878891175939; “Spring Revolution Daily News for 19th July 2021,” Mizzima Myanmar News and Insight, July 19, 2021, https://www.mizzima.com/article/spring-revolution-daily-news-19th-july-2021.

[50] “KO KO Jade Facebook Post,” Facebook, September 23, 2021,

[51] “Ministry of Health, National Unity Government of Myanmar 11/17/21 Facebook Post,” Facebook, November 17, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/MoHNUGMyanmar/posts/260774832748797.

[52] K Moe, “K Moe Facebook Post.”

[53] Nyein Swe, “ဖယ်ခုံတွင် စစ်ကောင်စီတပ်က ဆေးရုံဘက်သို့ လက်နက်ကြီးဖြင့် ပစ်ခတ်.”

[54] “Death Toll Underreported on Myanmar’s COVID-19 Frontline: Charities,” The Irrawaddy, July 8, 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/death-toll-underreported-on-myanmars-covid-19-frontline-charities.html.

[55] “Junta Tries – and Fails – to Use Pandemic to Tighten Grip on Power,” Frontier Myanmar, August 13, 2021, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/junta-tries-and-fails-to-use-pandemic-to-tighten-grip-on-power/.

[56] A Win, “Rapid Rise of COVID-19 Second Wave in Myanmar and Implications for the Western Pacific Region,” QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, October 23, 2020, hcaa290, https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa290.

[57] “MOHS Myanmar COVID-19 Surveillence Dashboard,” accessed January 20, 2022, https://www.mohs.gov.mm/ckfinder/connector?command=Proxy&lang=en&type=Main¤tFolder=%2FPublications%2FCOVID-19%2FSituation%20Report%20(CEU)%2F&hash=a6a1c319429b7abc0a8e21dc137ab33930842cf5&fileName=Sitrep%20262%20(25-12-2020)%20.pdf.

[58] World Health Organization (WHO), “Myanmar: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data,” accessed January 19, 2022, https://covid19.who.int.

[59] Shoon Naing, “Myanmar Prioritises Healthcare Workers as It Launches Vaccination Drive | Reuters,” Reuters, January 27, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-myanmar-vaccine/myanmar-prioritises-healthcare-workers-as-it-launches-vaccination-drive-idUSKBN29W0MS.

[60] Richard C. Paddock, “Virus Surges in Myanmar After Coup,” The New York Times, July 1, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/01/world/asia/covid-myanmar-coup.html.

[61] Asian Development Bank, “COVID-19 Active Response and Expenditure Support Program: Report and Recommendation of the President” (Asian Development Bank, August 24, 2020), Myanmar, https://www.adb.org/projects/documents/mya-54255-001-rrp.

[62] Shoon Naing, “Myanmar Prioritises Healthcare Workers as It Launches Vaccination Drive | Reuters.”

[63] Richard C. Paddock, “Virus Surges in Myanmar After Coup.”

[64] Richard C. Paddock; Jenny Lei Ravelo, “COVAX Allocates 17M AstraZeneca Vaccine Doses, but Details Are Hazy,” Devex, July 23, 2021, https://www.devex.com/news/sponsored/covax-allocates-17m-astrazeneca-vaccine-doses-but-details-are-hazy-100439.

[65]Civil Disobedience Movement, “We Are Not Exaggerating. The Military Is Ordering Oxygen Factories Not to Refill without Their Approval (Approval from a Local Army Commander). See the Photo below! We Need#R2P for Health Intervention. The Junta Is Content to Let People Die. #WhatsHappeningInMyanmar Https://T.Co/9iHkl0BGr0,” Tweet, Twitter, July 17, 2021, https://twitter.com/cvdom2021/status/1416316614778101761.

[66] “ဖားကန့် အောက်ဆီဂျင်စက်ရုံကို စစ်တပ်ကသိမ်းပိုက်၊ အရပ်သားများ ဖြည့်ခွင့်မရ” DBV, July 27, 2021, http://burmese.dvb.no/archives/477716?fbclid=IwAR062vMoQp1HA1nOC9vjXr4lYmIwcePF6AsQKhhPp8FADgJuGGSP6ryphtI.

[67] “ရန်ကုန်တွင် ဆေးဝယ်ရန် တန်းစီနေသူများကို ရဲက လူစုခွဲ,” Myanmar NOW, July 31, 2021, https://www.myanmar-now.org/mm/news/7648.

[68] Jonathan Head, “Myanmar Coup.”

[69] “Treating Covid Patients in Secret Myanmar Clinics,” France 24, December 27, 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20211227-treating-covid-patients-in-secret-myanmar-clinics.

[70] The World Bank Group, “Myanmar Economic Monitor: Progress Threatened, Resilience Tested” (World Bank Group, July 2021).

[71] UNDP, “Impact of the Twin Crises on Human Welfare in Myanmar” (UNDP, December 2, 2021), https://reliefweb.int/report/myanmar/impact-twin-crises-human-welfare-myanmar-november-2021.

[72] OCHA, “Global Humanitarian Overview 2022, Part Two Inter Agency Appeals: Myanmar,” (OCHA, December 2, 2021), https://gho.unocha.org/myanmar?fbclid=IwAR2W58DTT5YqHMOsTjMXvm6LCIOFz7jyqk_3M99gC6C45Ly-2jBH4YBEr1E

[73] UN Security Council, “Security Council Adopts Resolution 2286 (2016), Strongly Condemning Attacks against Medical Facilities, Personnel in Conflict Situations,” May 3, 2016, https://www.un.org/press/en/2016/sc12347.doc.htm.

[74] “Strengthening Respect for International Humanitarian Law,” France ONU, September 2019, https://onu.delegfrance.org/Strengthening-respect-for-international-humanitarian-law.