December 8, 2020

New alcohol guidelines for Australia

New alcohol guidelines have been released to help reduce the risk of alcohol harm and improve the health of Australians. The guidelines are based on the latest scientific evidence and have been developed by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

While there is no absolutely safe level of drinking, the guidelines do provide a framework for how to stay healthy and protect you and your family from alcohol harms.

Most people are aware that there is a limit to how much alcohol they can consume and still remain under the legal blood alcohol limit (BAC) when driving, but many of us aren’t so clear on the amount of alcohol we can consume before our drinking starts seriously impacting our health.

Why guidelines are helpful

It’s important that Australians who choose to drink get reliable facts on how to reduce the risk of harm from alcohol.

In the short term, harm related to drinking alcohol may include hangovers, headaches, nausea, shakiness, vomiting, memory loss, falls and injury, assaults, car accidents, unplanned pregnancy and accidental death.

Long-term harm from regular drinking include increasing the risk of eight different types of cancer, cirrhosis of the liver, brain damage, memory loss and sexual dysfunction.

By following the national guidelines, you can reduce these risks.

The new guidelines in brief

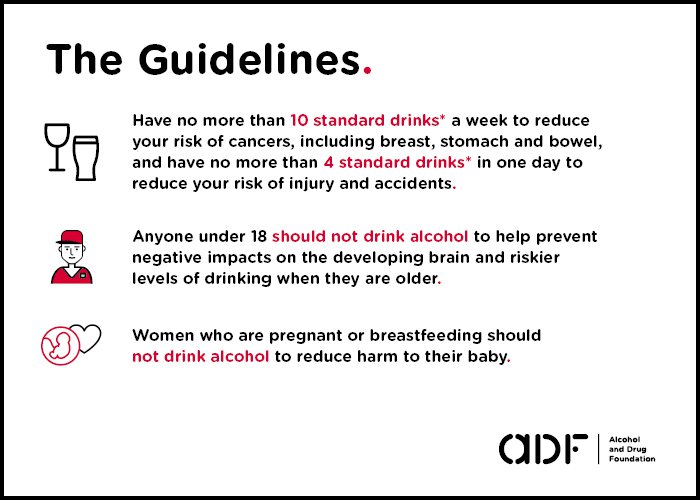

The guidelines recommend that:

- To reduce your risk of cancer, drink no more than 10 standard drinks a week.

- To reduce your risk of injury and accidents, have no more than 4 standard drinks in one day

- Anyone under 18 should not drink alcohol to help prevent negative impacts on the developing brain and prevent riskier levels of drinking when they are older.

- Women who are pregnant or planning a pregnancy should not drink alcohol to reduce harm to their unborn child.

- Women who are breastfeeding should avoid drinking alcohol as it is safest for the health and development of their baby.1

A standard drink might be less than you think – learn more about standard drinks.

The new guidelines in detail

Guideline 1: Healthy men and women

‘To reduce the risk of harm from alcohol-related disease or injury, healthy men and women should drink no more than 10 standard drinks a week and no more than 4 standard drinks on any one day.’

‘The less you drink, the lower your risk of harm from alcohol.’

The more alcohol you drink, the greater your risk of alcohol-related disease over the course of your life. If you drink no more than 10 standard drinks per week and no more than 4 standard drinks per day, your lifetime risk of dying from alcohol-related disease or injury is less than 1 in 100.

Guideline 2: Children and young people

‘To reduce the risk of injury and other harms to health, children and people under 18 years of age should not drink alcohol.’

For young people under 18 years of age, not drinking any alcohol at all is the safest option.

- This is because young people often drink more and take more risks increasing the likelihood of immediate harm such as injury and alcohol poisoning.2, 3

- Young people’s brains are still developing during their teenage years. Drinking alcohol may impact its development and lead to health issues later in life.3 The earlier a young person is introduced to alcohol, the more likely they are to develop these complications.

- Young people are also more likely to develop alcohol dependence later in life if they are introduced to alcohol early.3, 4 Young people should therefore delay their first drink for as long as possible.

Guideline 3: Pregnancy and breastfeeding

‘To prevent harm from alcohol to their unborn child, women who are pregnant or planning a pregnancy should not drink alcohol.’

‘For women who are breastfeeding, not drinking alcohol is safest for their baby.’

- Consuming alcohol while pregnant or breastfeeding can have harmful effects on the development of the fetus or infant.

- Prenatal alcohol exposure can increase the risk of complications such as bleeding, miscarriage, premature birth or stillbirth.5

- Alcohol can travel through the placenta to the unborn baby. As a result, prenatal alcohol exposure can cause a range of lasting physical, mental, behavioural, and learning disabilities for the baby.6 Read more about Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD).

- Alcohol can also pass into breast milk and reduce its availability. This can affect a baby's feeding and sleeping patterns and its development. Read more about pregnancy, breastfeeding, and alcohol.

Other factors to consider

Not drinking is the safest option if you are:

- involved in, or supervising, risky activities including driving, operating machinery or water sports

- supervising young people

You should get advice from your doctor about drinking if:

- you are taking any medicines, including prescription or over-the-counter medicines

- you have an alcohol-related or other physical condition, that can be affected by alcohol

- you have mental health issues

You may have an increased risk of harm if you:

- are under 18 years of age

- are over 60 years of age

- have a family history of alcohol dependence

- use illegal drugs.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. NHMRC; 2020.

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:111-26.

- Spear LP. Effects of adolescent alcohol consumption on the brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2018;19(4):197.

- McCambridge J, McAlaney J, Rowe R. Adult consequences of late adolescent alcohol consumption: a systematic review of cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2011;8(2):e1000413.

- Sundermann AC, Zhao S, Young CL, Lam L, Jones SH, Velez Edwards DR, et al. Alcohol Use in Pregnancy and Miscarriage: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2019;43(8):1606-16.

- Popova S, Lange S, Shield K, Mihic A, Chudley AE, Mukherjee RA, et al. Comorbidity of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2016;387(10022):978-87.