When Nia Martin-Robinson was 18, she had sex for the first time. Soon after, worried that she might have a sexually transmitted infection, she went to her local Planned Parenthood clinic in Detroit to get checked out. The clinician who examined her said she was healthy but added, “If you weren’t being promiscuous, you might not have to worry about having an STD,” recalled Martin-Robinson, who is Black. More than two decades later, the memory still stings. She had waited until high school graduation to have sex, just as her mother had asked. Yet here was a judgmental assumption coming from someone she’d sought out for medical help. “You can do all the right things and people’s bias will rear itself, whether that’s at a traffic stop or a room in a health center,” she said.

Today Martin-Robinson is the director of Black leadership and engagement at the national organization, Planned Parenthood Federation of America. She’s part of a new wave of Black women and women of color who are moving into leadership positions at a time when the organization as a whole is undergoing an internal reckoning around race, history, and the legacy of its founder, Margaret Sanger.

In June 2020, one of the network’s largest affiliates, Planned Parenthood of Greater New York, parted ways with its president and CEO of three years, Laura McQuade, amid allegations that McQuade was an abusive leader who bullied underlings and denied advancement opportunities to Black staffers. McQuade told The New York Times that the allegations against her were false but declined to refute them. The following month, the New York affiliate announced plans to remove Sanger’s name from its Manhattan health center because of her controversial support of eugenics in the 1920s and ’30s. Eugenics is the belief that human reproduction should be controlled to improve the gene pool and was used to justify such practices as institutionalization and sterilization of disabled people and anyone a government deemed undesirable.

In response to the allegations against McQuade, Planned Parenthood’s acting president and CEO, Alexis McGill Johnson, called on the board of the Greater New York affiliate to “hold themselves accountable to their mission and values by centering their patients, their staff, and their community.” She continued: “Right now our country is in the middle of a racial justice reckoning—one that includes Planned Parenthood. We know we cannot address structural racism or white supremacy in this country without addressing our own.” Soon after, McGill Johnson was named permanent president and CEO after nearly a year as the interim leader. She is the second Black woman to hold the position in the organization’s 104-year history. (Faye Wattleton served as president and CEO from 1978 to 1992.)

Joy D. Calloway, who is also Black, was named McQuade’s successor and interim CEO of the New York affiliate in October. “It is a radically transformed leadership team from when I joined a year ago,” Fiona Kanagasingam, the affiliate’s chief equity and learning officer, told me this fall. “We have a senior leadership team now that is majority people of color. The majority of people of color are Black. That did not happen by chance.”

The New York affiliate is training its staff in equity and anti-racism, and the national network is confronting its own shortcomings around race and power. This fall, news broke that an internal audit commissioned by Planned Parenthood found that dozens of current and former Black employees reported facing racism and discrimination from white colleagues while working for the organization.

For leaders such as Martin-Robinson, Kanagasingam, and McGill Johnson, Planned Parenthood’s mission to provide women with access to essential health care is critical, but it’s not the only thing worth fighting for. It matters how patients are treated once they arrive, and that Black staffers and people of color who work for the organization feel like they are being treated properly and equitably—an issue for which Sanger’s complicated history has become a flashpoint.

This year’s ideological battles over reproductive and racial justice have raged both in the courts and on the streets, but it wasn’t right-wing Internet heckling or propaganda campaigns that forced this sea change within Planned Parenthood. It was the work of those inside the organization who helped colleagues connect the dots between having one’s reproductive worthiness judged by a 20th-century eugenicist and being racially profiled in a 21st-century exam room while one’s feet are in the stirrups. This new generation of leaders is placing contemporary aggressions experienced by staffers and patients of color in the context of the damage done over generations, and is arguing for a rigorous reevaluation of the legacies of both Sanger and Planned Parenthood. For Martin-Robinson, this soul-searching is about “recognizing the multiple ways that white supremacy is in the fabric of what this country is and [in] the institutions that rise out of that.”

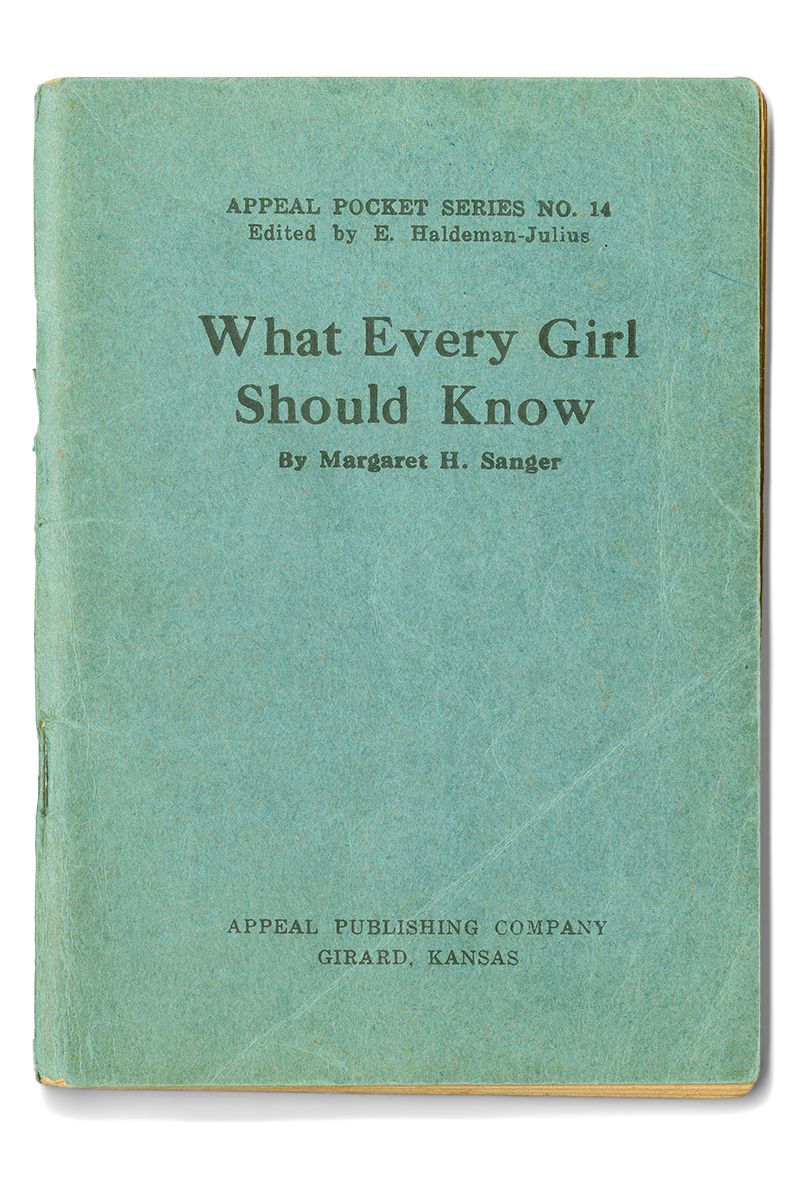

In 1916, Sanger, a women’s health advocate, opened the first clinic in the U.S. to offer contraception. Birth control wasn’t just taboo at the time—state and federal Comstock laws, which deemed contraceptives as “obscene,” made it illegal even to distribute information about it. Sanger’s clinic in Brooklyn’s Brownsville neighborhood was the predecessor of Planned Parenthood’s New York City affiliate, the first in the national network. Today it is part of the Greater New York affiliate, which has 30 locations serving 65 percent of the state. The larger network consists of 49 affiliates and more than 600 health centers around the U.S.

Sanger has long been celebrated by many as a feminist hero who gave women more control over the size of their families, their bodies, and their lives. But for others, Sanger’s support for eugenics is troubling, linking her to a painful history of medical abuse and reproductive coercion in the U.S.—one that includes the forced breeding of enslaved women in the Antebellum South and the mass sterilization of Puerto Rican women throughout the 20th century.

Too often, Sanger’s critics say, Black and Latinx communities have suffered because of eugenicist policies and thinking. But to those who view Planned Parenthood’s founder as a trailblazer, the New York affiliate’s decision to remove her name has been baffling: She was a woman who promoted contraception as a way to prevent women from having to seek out the illegal and often dangerous abortions that were available in her day. Sanger’s defenders also worry that the move to dissociate themselves from her work by removing her name from the Manhattan health center signals a caving of sorts by Planned Parenthood to pressure from anti-choice activists, who in recent years have portrayed Sanger as a villainous character in their abortion wars. Staffers at the national and New York offices repeatedly told me that the right wing has “weaponized” Sanger against the organization, holding her up as proof of Planned Parenthood’s disregard for communities of color and its commitment to controlling and limiting Black births.

In 2016, the year Planned Parenthood celebrated its centennial, the organization published a fact sheet intended to clarify Sanger’s relationship to eugenics. Sanger, the document explained, “clearly identified with the broader issues of health and fitness that concerned the early-20th-century eugenics movement, which was enormously popular and well-respected by doctors, physicians, political leaders, and educators during the 1920s and ’30s.” Despite Sanger’s involvement in the movement, efforts to tie her to some kind of white supremacist agenda were wrongheaded, the organization argued at the time. Sanger wanted Black women to have the same access to birth control as white women.

But the focus on the mainstream acceptance of eugenics has long frustrated advocates of reproductive justice, a movement founded in 1994 by Black women that puts the right to not have a child on equal footing with the right to have a child—and under safe and healthy conditions, in communities that will sustain them. As a movement concerned with the experiences of Black women and women of color, reproductive justice leaders have provided an alternative framework for understanding this history. Lynn Roberts, an associate dean at the City University of New York’s Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy, told me about Sanger’s defenders, “They’ll often say, ‘That wasn’t unusual for this period.’ Sometimes that comes across as excusing her.”

Sanger’s biographer Ellen Chesler, author of the 1992 book Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America, has made it her mission not to defend Sanger’s relationship to eugenics but to help explain it. When we spoke in September, Chesler offered: Eugenics was a politically neutral movement; there were conservative and liberal eugenicists. Sanger, a Socialist, was among the latter. While those on the right wanted to limit fertility on the basis of racial and ethnic identity, those on the left believed ability and talent were universal. “Imbeciles,” “morons,” and “the feebleminded”—words Sanger and other eugenicists used frequently—could be of any background. At the invitation of Black leaders including the Reverend Dr. Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., of Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, and Mary McLeod Bethune of the National Council of Negro Women, Sanger worked to make contraception available to Black women in the North and South. “In order to build a bigger tent for Planned Parenthood she had to enter the eugenics conversation, which was ubiquitous in the 1920s,” Chesler said.

NAACP cofounder and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois, who was an adviser to Sanger, also believed in a democratic meritocracy—a “Talented Tenth” of Black people, who were innately exceptional and should be educated and invested in so they could lead the race, a position that drew criticism even in his day. “Should we call him a racist for that?” Chesler said. “I don’t know. I think that’s nuts.”

Du Bois needn’t be deemed racist, said Roberts of CUNY. But we should reckon with his elitism. Eugenics was wrong, no matter who promoted it. “Having fewer children shouldn’t be the solution,” Roberts said. Instead, she said, people then as now should decide for themselves their family size, and state support shouldn’t be withheld if a family is larger than deemed appropriate by some outside observer. What’s important is that people “have bodily autonomy to make those decisions for themselves,” Roberts said.

Explanations like Chesler’s don’t sit well with those who support the name change, including Martin-Robinson, who are quick to point out that eugenics programs were put in place during the Jim Crow era, with its entrenched racial hierarchies and doctrines about biological differences between the races. “Even if states were saying, ‘We are involuntarily sterilizing people who we consider to be feebleminded,’ there was so much connection with people’s ideas around mental ability and race,” said Martin-Robinson. “I find it difficult to separate eugenics from racism.”

Still, the link between Sanger and eugenics has led to assertions about Planned Parenthood that are false and need to be challenged outright. Sanger was a eugenicist, yes, but Planned Parenthood offers much needed health services in Black communities, Martin-

Robinson said. “Both of those things can be true at the same time.”

In the past decade, anti-choice activists have waged a series of disinformation campaigns that depend on Americans—especially Black Americans—not being able to make that distinction. Maafa 21: Black Genocide in 21st Century America, a 2009 documentary directed by white anti-choice activist Mark Crutcher, stitches together a conspiracy in which Sanger deliberately placed clinics in Black neighborhoods to reduce Black births and was allied with Adolf Hitler. The film has been screened on the campuses of historically Black colleges and universities and in Black churches in an effort to persuade people that a disproportionate number of Black women get abortions not because of institutional barriers that result in unplanned pregnancies but because of a sinister plot on the part of Planned Parenthood. Not long after its initial release, billboards began going up—first in Atlanta and then nationwide—with messages such as “Black children are an endangered species,” and “The most dangerous place for an African American is in the womb.” Anti-choice groups such as Georgia Right to Life, the Radiance Foundation, and Life Always were behind the signs, often installed in states where legislation intended to restrict access to abortion had been introduced.

The Planned Parenthood staff members who called for and welcomed the removal of Sanger’s name say they aren’t responding to right-wing pressure. But they don’t pretend to be immune to it either. Staffers shared with me experiences of walking into health centers and being shouted at by white anti-abortion protesters who questioned their commitment to Black lives. “We are the target of a lot of vitriol,” Kanagasingam of the New York affiliate told me of women of color who work at or receive health services from Planned Parenthood. “This consistent use of Sanger by anti-abortion activists under the guise of caring about Black people and Black women is offensive. It is ill-informed. It’s inflammatory. And it continues to infantilize Black women,” Martin-Robinson said. “It feeds into this continuous myth around the necessity to control Black people because they do not have the intellectual means or capacity to take care of or control themselves.”

Martin-Robinson supported the staff of Planned Parenthood in New York as they planned Reviving Radical, an ongoing series of events started in late 2019 and early 2020 designed to help the local affiliate begin to repair its relationship with the communities of color it primarily serves. At each meeting, dozens of people from around New York City—mostly Black and Latina women—gathered at carefully selected locations (a YMCA in Downtown Brooklyn, the Malcolm X & Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Education Center in Washington Heights, Hostos Community College in the South Bronx) to share stories of being mistreated by health-care providers at Planned Parenthood clinics. The testimony was facilitated by activists, scholars, and clinicians with deep roots in reproductive justice. Top brass at the affiliate, including the chief executive and chief medical officers, were there to listen and learn. Merle McGee, architect of the gatherings and the affiliate’s chief equity and engagement officer, describes the process as one of “truth and reconciliation,” a phrase popularized in post-apartheid South Africa.

Martin-Robinson said listening to others share their stories brought back memories of her own experience as an 18-year-old at that Detroit Planned Parenthood clinic in the late ’90s. When it happened, she had some context for the slight. Martin-Robinson was introduced to the history of white supremacy in reproductive medicine early. “I learned about eugenics, forced sterilization, and the attachment of population restrictions on International Monetary Fund grants from my own mother, who was not a Margaret Sanger fan,” she said. “Despite that, [she] supports my work here because she realizes that folks in our community need access to sexual and reproductive health care.”

Martin-Robinson’s understanding of the prevalence of eugenicist thinking deepened while she was on staff at the Sierra Club, where she was often approached by middle-aged white men who would ask about population control as a way to save the environment. “Clearly I’m a sucker for a 100-year-old organization,” she told me. She turned to the reproductive justice movement, whose adherents were grappling with “what it meant when our bodies were used to further particular agendas,” she said. “They had the language around what it meant for us to be able to have bodily autonomy and control.”

The relationship between the reproductive justice movement, with its inclusion of the right to parent as a central tenet, and the reproductive rights movement, with its traditional focus on a woman’s right to not have a child, is complex.

In August 2014, there was an exchange of open letters between Monica Simpson, executive director of the Atlanta-based reproductive justice collective SisterSong, and Cecile Richards, then president and CEO of Planned Parenthood. In interviews with The New York Times and an op-ed placed in The Huffington Post, the national leadership at the time signaled their move away from the term “pro-choice” in favor of more expansive language about women’s health and economic security. In response, Simpson and dozens of individuals and organizations that signed her letter took Richards to task for what Simpson called “the co-optation and erasure of the tremendously hard work done by Indigenous women and women of color (WOC) for decades.” After all, this broadening of the frame beyond abortion had long been the work of reproductive justice activists, but white women were being credited with the strategic shift in the paper of record.

Planned Parenthood’s more recent commitment to valuing the leadership and expertise of women of color—both staff and patients—is what’s significant, said McGee. She called the removal of Sanger’s name from the Manhattan health center “the shiny ball” that’s drawn attention and provoked debate. But it’s only one part of a larger shift happening in the organization. “We’re now in the deep waters,” McGee told me as she described the Reviving Radical meetings and internal changes at the New York affiliate. “That’s where the radical transformation happens, by looking at who we partner with and how.”

In October, the Senate confirmed the nomination of conservative jurist Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, to fill the seat of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. It was a victory for anti-choice activists, confident that overturning Roe v. Wadeis within their reach. Anti-choice state lawmakers continue to pass damaging laws that close clinics and otherwise restrict abortion, and reproductive rights are in peril nationwide. The disinformation campaign against abortion in general and Planned Parenthood in particular continues unabated online.

Some might assume that persistent attacks from those who oppose access to sexual and reproductive health services would make Planned Parenthood staffers close ranks, play it safe, and stay quiet so as not to attract additional controversy. Instead something else entirely is happening at national headquarters and the largest affiliate. The organization is confronting long-simmering debates head-on, distancing itself from Sanger, instituting anti-racism training, and conducting internal audits to hear what’s really on Black employees’ minds. Bold steps are being taken not away from past harms and humiliations but toward them in an effort to acknowledge and root them out. For Martin-Robinson, it’s the memory of her experience at that clinic years ago that drives her commitment to Planned Parenthood. “I work here because of that,” she said, referring to the shame that clinician tried to heap on her as a teenager. “To make sure that Black and brown girls are able to go into our health centers and get the kind of quality, compassionate care that we deserve.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2020/January 2021 issue of Harper's BAZAAR, available on newsstands December 1.

GET THE LATEST ISSUE OF BAZAAR

Use the code HOLIDAY50 at checkout for a special, limited time 50% discount.