Understanding Orca Culture

Researchers have found a variety of complex, learned behaviors that differ from pod to pod

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Luna-Orca-Culture-underwater-631.jpg)

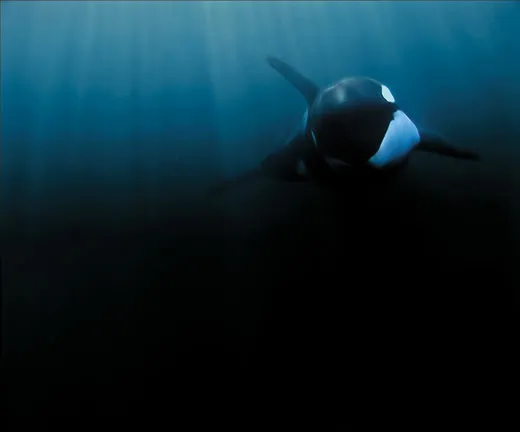

Orcas have evolved complex culture: a suite of behaviors animals learn from one another. They communicate with distinctive calls and whistles. They can live 60 years or more, and they stay in tightknit matrilineal groups led by older females that model specific behaviors to younger animals. Scientists have found increasing evidence that culture shapes what and how orcas eat, what they do for fun, even their choice of mates. Culture, says Hal Whitehead of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, “may be very important to them.”

Some of the first evidence of cultural differences among orcas came from studies of vocalizations in whales that frequent the coastal waters of British Columbia and Washington State. Such “residents” belong to four clans, each with multiple groups. While the clans live close together—their ranges even overlap—their vocalizations are as different as Greek and Russian. And smaller groups called pods have dialects akin to a Southern drawl or a clipped New England accent.

Among orcas, food preferences tend to be distinct. Resident orcas, researchers found, eat chinook and chum salmon. And orcas share meals, particularly between mothers and offspring. A mother orca—a 7,000-pound behemoth—will hold a salmon in her mouth while her calves chew on it. And thus the group’s preference for chinook may be transmitted to the next generations. “Transient” orcas, which swim in the same waters as residents but roam more widely, hunt marine mammals such as seals, porpoises and sea lions. “Offshore” orcas, which are found ten miles or more from shore from Alaska to California, eat so much shark their teeth get worn to the gums from chewing their prey’s sandpapery skin. In Antarctica, one orca population prefers penguins, while another likes minke whales.

Other behaviors vary from group to group. Some resident killer whales in British Columbia frequent “rubbing beaches” where they scrape along pebbly rocks; other groups in the same waters don’t go in for body scratching. Residents in the Salish Sea (coastal waters around Vancouver Island and Puget Sound)—the group to which the young Luna belonged—have a reputation for being unusually frolicsome. They wag their tails, slap their pectoral fins and “spyhop”—bob into the air to get a better look at the above-water world. They also engage in “greeting ceremonies” in which whales line up in two opposing rows before tumbling together into a jostling killer whale mosh pit. “It looks like they’re really having a great time,” says Ken Balcomb, a biologist with Washington’s Center for Whale Research.

But adhering to strict cultural norms can have serious consequences. While there are about 50,000 orcas worldwide, the Salish Sea’s residents are down to fewer than 90 animals—and social mores appear to prevent them from mating outside their group, creating an inbred population. Meanwhile, though the residents’ preferred food, chinook, is scarce, the orcas’ upbringing seems to make them reluctant to eat sockeye and pink salmon, which are abundant.

“The rules hold,” says Howard Garrett, co-founder of Orca Network, a Washington-based educational organization. “They depend on their society and live accordingly by old traditions.”

Lisa Stiffler is an environmental writer in Seattle.