Announcing the winner of the 2022 Bernard Lown Award!

Watch the Bernard Lown Award ceremony, featuring remarks from BLASR winner Mona Hanna-Attisha, Lown Institute President Vikas Saini, and Zachary Lown, grandson of Dr. Bernard Lown.

The Bernard Lown Award for Social Responsibility, created in honor of Dr. Lown after his death in 2021, recognizes young clinicians who stand out for their bold leadership in social justice, environmentalism, global peace, or other humanitarian efforts.

The Lown Institute is proud to announce Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha as the winner of the inaugural Bernard Lown Award for Social Responsibility. The award, including a $25,000 prize, will be presented on June 7, 2022 at an award ceremony. (View press release)

Mona Hanna-Attisha is a pediatrician, author, and activist best known for exposing the Flint water crisis and her continuous work to improve the health of Flint children and children everywhere. She is founder and director of the Pediatric Public Health Initiative, an innovative and model public health program in Flint, MI.

Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha’s Story

Mona Hanna-Attisha is born on December 9

Born to Iraqi scientists in Sheffield, England, Mona and her family soon move to Royal Oak, Michigan.

Receives her M.D.

After graduating from Michigan State University College of Human Medicine in East Lansing, MI, Dr. Hanna-Attisha went on to complete her pediatric residency. A few years later, she earned her MPH in Health Management and Policy from the University of Michigan School of Public Health in Ann Arbor, MI.

Named Assistant Professor

Not long after completing her pediatric residency, Dr. Hanna-Attisha is named Assistant Professor in the Department of Pediatrics and Human Development at the College of Human Medicine at Michigan State University in Flint, MI

Flint, MI switches the water supply

On April 25, the city of Flint changes its primary water source to the Flint River. Soon after the switch, residents begin complaining about dark colored, smelly water as well as rashes and hair loss. Without their knowledge, lead was leaking into their water supply and making them sick. The water was so corrosive that it was eroding the machines at the nearby General Motors and disrupting production. By October, GM announced it would stop using Flint water in its factories.

First city hall meeting about the water

On January 21, Flint residents haul containers of brown, smelly tap water into City Hall, demanding to know if it is the cause of their new ailments. City officials insist the water is safe. Just two months later, the City Council voted to reconnect Flint to its original water system – but this decision was overruled by the city’s emergency manager, maintaining that there is nothing wrong with Flint water.

Blowing the whistle on the crisis

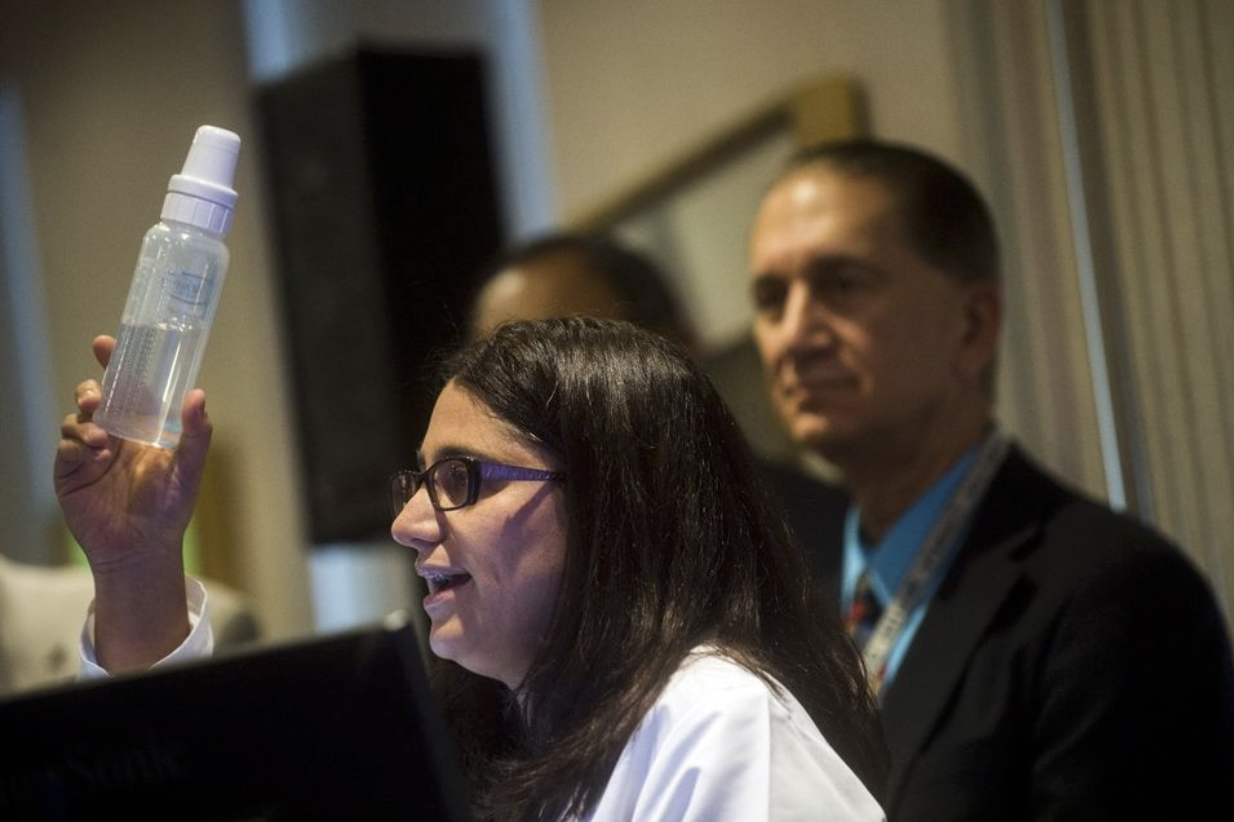

On September 24, Dr. Hanna-Attisha held a press conference at Flint’s Hurley Medical Center, where she revealed her findings: the children of Flint’s blood lead levels had doubled after the water was switched. She urged residents to stop drinking the water immediately. City officials respond by attempting to discredit her, accusing her of manipulating data to cause chaos.

Findings are confirmed by MDHHS officials

While the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services had dismissed Dr. Hanna-Attisha’s findings at first, officials confirmed her findings on October 2. Governor Rick Snyder announces a plan to ensure residents have access to clean, safe water and approves $9 million in funding to address the crisis. By October 16, residents are reconnected to their original water source – but are soon told that proper anticorrosion control measures were not implemented by the state, and the lead levels would stay high for over a year.

Founding of the Pediatric Public Health Initiative

In January 2016, Dr. Hanna-Attisha, alongside Michigan State University and Hurley Children’s Hospital, founded the Pediatric Public Health Initiative (PPHI) to address the Flint community’s population-wide crisis and help all Flint children grow up healthy and strong.

Congress addresses the Flint water crisis

Dr. Hanna-Attisha testifies in front of Congress on February 3. A few months later, President Barack Obama visited Flint personally to hear more from the residents about the water crisis. In December the House Republicans complete their investigation, concluding that Michigan State Officials and the EPA are both at fault for failing the citizens of Flint. The Senate allocates $100 million in funding to support efforts in fixing the crisis.

Universal screening program for the impact of the crisis on local kids

In April, an agreement between the state officials, education officials, and attorneys for Flint’s schoolchildren is reached to establish a program to provide universal screenings for learning disabilities to all Flint children impacted by the city’s water crisis. At this point, Flint kids are still drinking bottled or filtered water.

What the Eyes Don’t See

This memoir written by Dr. Hanna-Attisha describes her fight to get the Flint city officials and Michigan state officials to acknowledge and fix the water crisis.

C.S. Mott Endowed Professor of Public Health

Dr. Hanna-Attisha becomes an endowed professor at the Division of Public Health in the College of Human Medicine at Michigan State University in Flint, MI

Inaugural BLASR Award

On June 7, Dr. Hanna-Attisha wins the Bernard Lown Award for Social Responsibility in medicine. As of this time, the US Environmental Protection Agency is still recommending that Flint residents always use a water filter. Without Dr. Hanna-Attisha’s advocacy and strong sense of social responsibility, the EPA may never have even acknowledged the water crisis and Flint residents would still be suffering in silence.