Listen to What Next:

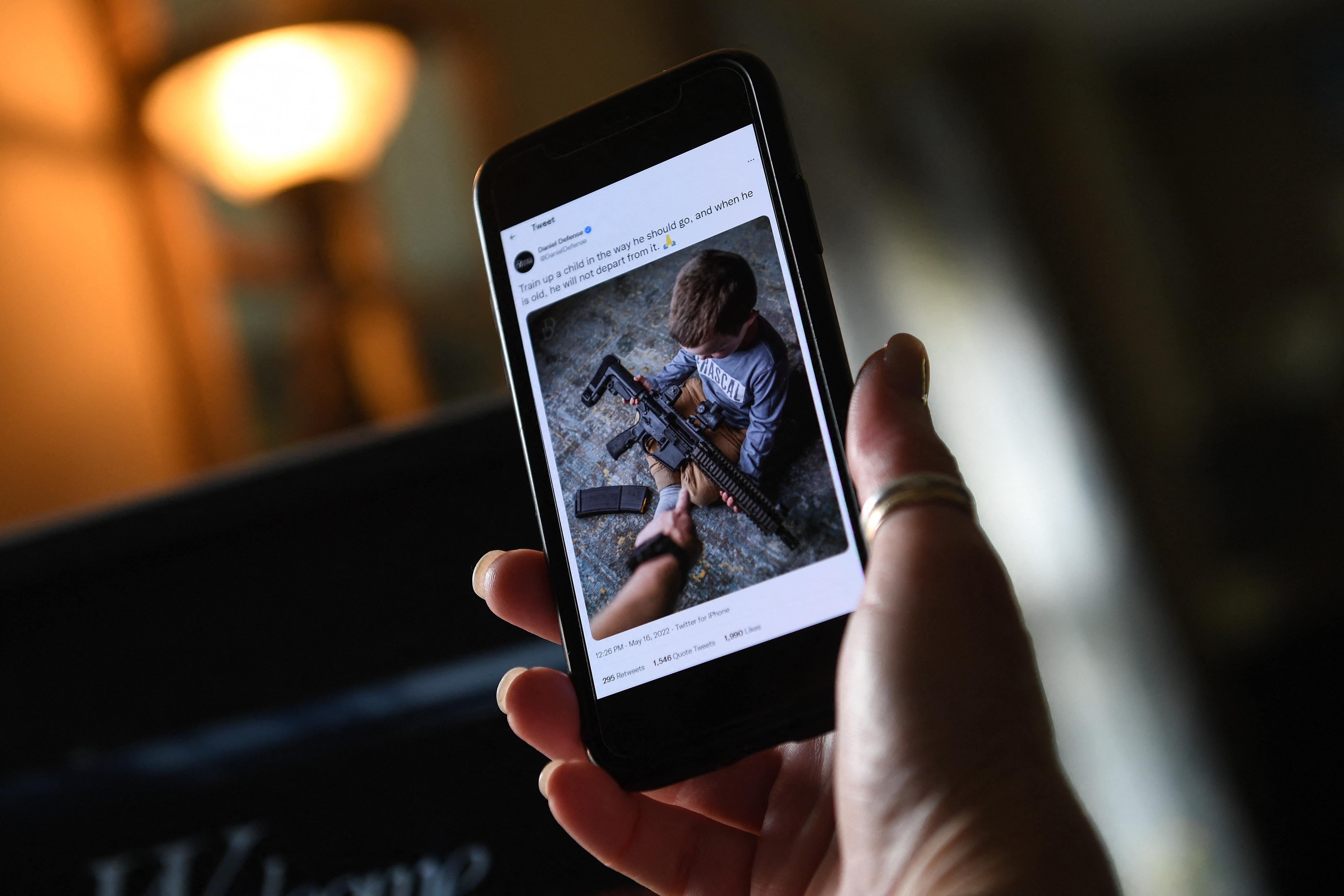

On May 16, the gun company Daniel Defense tweeted an ad featuring a toddler holding an AR-style rifle—the same kind of gun that would be used to kill 21 people in Uvalde, Texas, days later. According to Todd C. Frankel, an enterprise reporter at the Washington Post, ads like these are as routine as the “thoughts and prayers” Daniel Defense and other gun companies offer up after every mass shooting. There is “a Groundhog Day quality to all this,” he says. “They just follow the same playbook and no variation.” On Thursday’s episode of What Next, I talked to Frankel about why gun manufacturers aren’t worried about bad publicity and how guns became identity politics. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Mary Harris: Can you just introduce me to Daniel Defense and the people who run it? It’s a relatively new manufacturer, right?

Todd C. Frankel: Yeah. They are part of this explosion in gun companies we’ve seen nationwide after the assault weapons ban was repealed in 2004. After that ban was lifted, a lot of room for innovation. There’s an entirely new product line that could be introduced and sold to people, this semi-automatic rifle that looks like it came from the military. And so all these smaller gun manufacturers rushed in to fill this space.

Daniel Defense was started by Marty Daniel—it’s named for him. He’s a guy who lives outside Savannah, Georgia, and he started his company in 2001. He’s an engineer. … Started off with a military contract, supplying the military with one part for one of their rifles, and just kept on growing from there and eventually started introducing his own line of weapons.

Cheeky marketing sort of became baked into Daniel Defense as it got bigger and bigger. What does an ad for a Daniel Defense weapon look like, and how does it compare to an ad for another weapon?

Their ads, they’re definitely different than you would see from like a hunting rifle sort of ad, the deer and the guy out in the woods and sort of sitting in a tree stand. Theirs is more aggressive. There’s a twinge of religiosity to it as well. There’s been an interesting crossover with guns and Christianity, sort of hardcore, like this belief of protecting your family and this is one of those God-given rights, to arm yourself.

A lot of children with guns in their ads.

Within the culture, it doesn’t look as strange. Outside, yes, it looks really bizarre. A week before the Uvalde shooting, they had an online social media ad where there’s a toddler sitting crisscross applesauce on the floor with a rifle on his lap. It’s clearly unloaded. There’s a finger pointing at him, and there’s a proverb quoted above him sort of saying, you know, teach him well now and you won’t have to teach him later. Which reads very bizarrely to outside the gun culture.

There’s a lot of stressing on freedom, too. I think one of their taglines is “manufacturing freedom,” and this idea that the gun industry and guns are constantly under threat and there’s no bigger way to show that you support America and freedom than owning one of these guns. That’s a really important marketing tactic to moving these.

So companies kind of created or worked within a culture that would seem bizarre to someone outside of it, but inside of it, it makes complete sense. It’s part of what’s strange after a shooting like this.

Yeah. It’s completely jarring and even offensive in some ways, when the outcome is murdered kids. And then in their marketing they have young kids and you’re like, well, jeez, what the heck is going on here?

And there’s a backlash to it. There’s folks even within the gun industry who I talked to, some on the record, some off the record, who are uncomfortable about this, this sort of shift within the industry, that it’s going too far in trying to sell its weapons in its marketing, especially when you have these horrible outcomes later on.

Yeah, one gun critic said Daniel Defense is a perfect illustration of the growing extremism in the gun industry. Do you think that’s a fair assessment?

Yeah. The rifles that they sell and even the pistols … they, to the ordinary eye, do not look like pistols and they look like just smaller semi-automatic military rifles. And the couch commando industry of these folks who sort of want to playact soldier and want to have this real aggressive—it’s like the guy who drives the big muscle truck with the big muffler and the Calvin pissing on the Ford logo. It’s like the Marlboro Man, a tough, rugged guy, and what you do if you’re tough and rugged is you get this really aggressive rifle and it’s, quite frankly, probably what attracts a lot of these mass shooters to using it too. They’re angry, disaffected. Let’s get the most macho thing out there.

How much of this marketing is about Marty Daniel, and how much of it is just about the industry changing?

It’s sort of the chicken and egg. Is Marty Daniel pushing this, or is he sort of shaping his image to go along with what is in demand? He’s even known, within a sort of loud industry, as a bombastic figure, loud and aggressive with his sales pitch. He really enjoys this position of gun as totem in the culture wars … playing up the showmanship of it and pushing the envelope perhaps sometimes with his marketing.

Are there ways other than marketing that you see Daniel Defense as an interesting illustration of bigger trends in the firearm industry? You mentioned this company is headquartered in Georgia, which is where Marty Daniel lives, but for many years the South was not the cradle of gun manufacturing in the United States. Is that changing, too?

Yeah, that definitely is changing. The sort of cradle of American gun-making for a really long time was the Northeast, in and around Springfield, Massachusetts. Smith & Wesson, it’s a publicly traded company, it’s huge, they’ve been based forever in Springfield, Massachusetts. And they announced late last year that they are moving operations to Tennessee. In part they probably blame the gun restrictions in Massachusetts and they said Tennessee is much friendlier to the Second Amendment. And that is partly true. But also, it’s an economic development issue. They were lured there by the state and they’ll face lower taxes.

But it’s tougher for the gun manufacturers who are still located in those areas, as guns are more and more a cultural war issue. After the Parkland shooting, the shooter used a Smith & Wesson AR-15-style weapon. And there were protests outside of the Springfield, Massachusetts, headquarters of Smith & Wesson. These jobs are good-paying, solid jobs. But there were students and other people who were just out there protesting, angry. Smith & Wesson’s probably not going to face protests like that when they move to Tennessee.

This bifurcation in the country … it becomes sort of crystallized when you look at what’s happening in the gun industry.

Certainly. We talk about blue states and red states, and folks are self-sorting themselves into neighborhoods where their like-minded neighbor is along political lines. And guns are very much a political issue. It’s not like Democrats don’t own guns and there aren’t even aggressive Second Amendment Democrats. But it has become very much a sort of symbol on the right.

When right-wingers want to intimidate folks in public, the open carry, the AR-15 slung over the shoulder is the image that is projected out there, and there’s a reason for that, because that weapon’s incredibly aggressive. And so you have these gun manufacturers then sort of self-sorting and choosing to relocate. In some ways, these issues get harder to solve when we are divided across geography like that.

Has Marty Daniel ever shown support for greater gun control measures?

Once, he did. And his customers did not appreciate it.

What happened?

The 2017 Sutherland Springs, Texas, shooting, [the shooter] never should have actually been able to buy the weapons he bought. And so in 2018, a bill sponsored by Republicans, who are loath to tighten gun control measures, they supported a bill to require and encourage more information to be fed into the background check system, so things like this would be caught. And Marty Daniel came out and supported that. You know, hey, let’s keep folks who shouldn’t have guns from getting guns, this is part of law. And there was a huge blowback, as customers were like, this is a Trojan horse—I mean, everything’s a Trojan horse to absolutists on the gun rights issue. Any sort of giving an inch, you know, oh, my God, they’re going to come for your guns next. And it’s really a very tough negotiating position.

So they came at him and he backtracked. He said, I’m sorry, I didn’t really think this through, I shouldn’t support this bill. And he didn’t support it. Notably, the Republicans and Democrats passed this bill and President Trump signed it.

It was the one time that I saw where Marty Daniel didn’t follow the script that we so often see the gun industry follow. What I’ve heard from others is that you don’t step out of line. You know, in the gun industry, you have to sort of follow the line that all gun control measures are bad.

There’s a strange incentive structure for gun manufacturers that you’ve nodded to. Like after a mass shooting, sales of firearms go up. Marty Daniel actually told Forbes that the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary drove a lot of sales, which is a really ugly fact. The stock price of Smith & Wesson rose 8 percent in the days following the shooting in Uvalde. Do we have a good idea of how these kinds of incentives influence company decision-making?

So much of the gun industry’s sales and marketing is driven on fear. Fear that someone’s going to break into your house. Fear that you’re going to get accosted by a rapist. Fear that the feds are going to come and take your guns, there’s going to be more gun control measures. And so yeah, there’s this perverse effect of these mass shootings where they drive stock prices, they drive sales, people get freaked out.

There’s an inverse to that too. When Hillary Clinton lost unexpectedly to President Trump, the gun industry had been ramping up production, expecting Hillary Clinton to win and expecting gun control to be a main problem and feature of the debate. And that didn’t happen. And the so-called Trump slump hit and these gun manufacturers really suffered. Some even went bankrupt. Because fear drives sales, and there was no longer fear of gun control with a Republican in the White House.

You’ve said yourself a responsible gun owner might look at the fact that Daniel Defense manufactured a weapon used in mass shootings and say, listen, this isn’t the company’s fault, it makes a tool that can be used responsibly or irresponsibly. How is Daniel Defense different from, say, Budweiser selling someone beer and then they crash their car?

That’s the argument you hear a lot from Second Amendment supporters. “You don’t hear them doing anything about that other stuff,” you know? But we do. It’s like, well, actually, Budweiser took a lot of heat for drunk driving and it now runs ads encouraging you to designated driver. There’s been a lot of pushback and lawsuits against bartenders for overserving people. And for automobiles, we have a licensure system, an insurance system.

Shortly after the assault weapons ban was repealed, Congress also passed basically an immunity shield, a liability shield for gun-makers, so that people can’t sue for some of these sort of overreaches and stuff like that. So imagine if Ford or GM or Honda had that too, where you couldn’t sue when the car is being used repeatedly in bad ways. But we have seatbelts, we have airbags, we’ve done all these things to try and make these things safer. And there is nothing to make guns safer. If anything, we are trying to make guns riskier and more lethal. And that’s the selling point.

The mass shooting at Sandy Hook opened the door to some kind of accountability for some companies. Families sued the Remington company, which made the gun that was used in the massacre. And this lawsuit created a kind of blueprint for suing other gun-makers. It was all based on state law because there’s the federal protection that you alluded to there. Is there any evidence that Daniel Defense is thinking about that as a potential liability?

No sense that necessarily Daniel Defense is thinking about that at the moment. These lawsuits do get filed after shootings, and what was notable at the Sandy Hook one against Bushmaster and Remington, the maker of the rifle used there, was how far it did progress. But notably, it was settled last year for I think $73 million.

So they didn’t win.

Right. They didn’t actually have the judges decide in their favor. And the gun industry is very quick to point out that the insurance companies of the gun manufacturers settled this, and so they are not taking this as any sort of message.

But it’s really interesting to think about if they did not have this liability shield. I mean, they said it was for … nuisance lawsuits. But there is some real liability here, when you market your weapon in such a way and just let it out into the wild and then something happens. Without that shield, I think they’d be in a huge bunch of trouble.

I kind of have the sense that the financial power of the gun industry and its lobby is weakening. But does the evidence show that the power of the gun industry is changing or weakening in any way?

I think it’s changing. You’re right, the NRA has been hobbled by its bankruptcy and Wayne LaPierre being criticized for his leadership style. I think it’s notable, though, that, like, Mike Bloomberg’s Everytown for Gun Safety is also a major contributor on the other side.

Everyone wants to blame the NRA. It’s not just a political money issue. It’s a cultural issue. It’s an identity issue for a lot of folks, especially on the right. It is now sort of a culture issue where the money almost doesn’t matter in some ways. This is part and parcel of your identity.

One former gun industry executive you spoke to compared the gun industry to the opioid industry. I wondered what you made of that.

The opioid industry went from making this miracle drug that was hailed and was a breakthrough for treating the pain of cancer patients and stuff. And they got a little heavy in their marketing. They wanted to find a bigger market for their product and they started pushing it out to perhaps places they shouldn’t, into pain clinics and script mills, and it became a huge issue that fed this other broader epidemic of heroin and addiction. But it started with a very legitimate company selling something that was very legal and well thought of and just going too far.