Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell has no intention of releasing an agenda for Senate Republicans ahead of the midterm elections.

What’s the point? All the out-party has to do during a midterm election cycle is keep the attention focused squarely on the failings of the party in power, and then reap the benefits. To issue an agenda—which wouldn’t go anywhere under a divided government, anyway—would be to turn the spotlight away from the other party’s lousy ideas and onto your own.

McConnell knows this, which is why, when asked about the Senate Republicans’ midterm agenda in January, he responded with a knowing, almost snarky acknowledgment of the political dynamics.

“That is a very good question,” McConnell said. “And I’ll let you know when we take it back.”

McConnell may be irked, then, that a member of his leadership team released an agenda of his own on Tuesday morning.

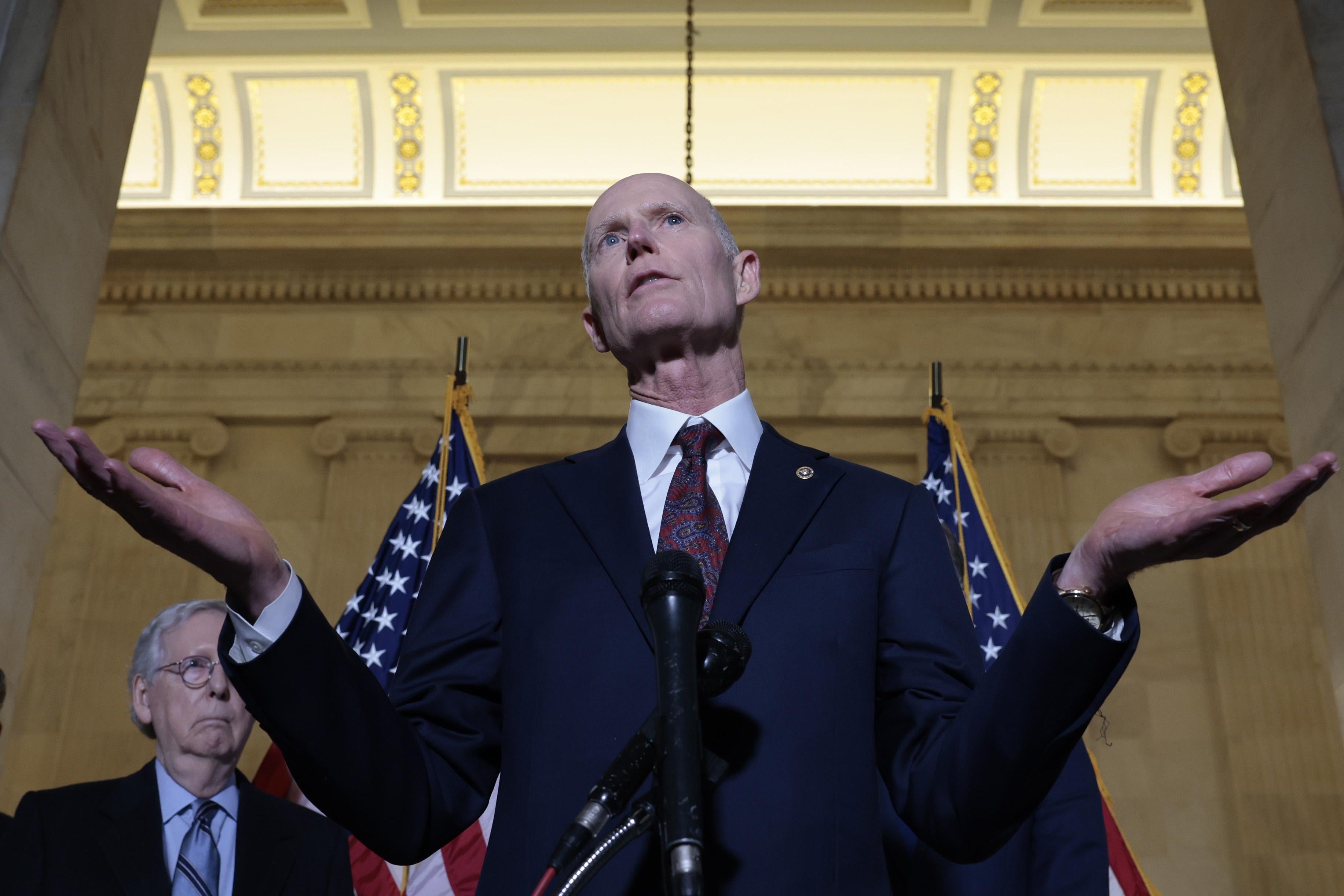

Florida Sen. Rick Scott unveiled his “11 Point Plan to Rescue America,” as he told Politico, to ignite “more of a conversation about what Republicans are going to get done.”

“There’s things that people would rather not talk about,” he added. “I’m willing to say exactly what I’m going to do. I think it’s fair to the voter.”

The document is largely a compilation of culture war grievances. An introductory slide titled “THE HOUR IS LATE IN AMERICA,” backgrounded by a photo of a burning Constitution, speaks of how “we are allowing biological males to destroy women’s sports,” for example. The same slide that calls for abolition of the Department of Education because “education is a state function” also describes a litany of curriculum items that school systems must and must not teach.

But wedged between the cultural huffing and snorting, there are some policy prescriptions that you might hear about for the rest of the campaign cycle—in attacks from Democrats.

Near the end of the Economy/Growth section, for example, there’s a call to raise taxes on half of the country. “All Americans should pay some income tax to have skin in the game, even if a small amount,” it reads. “Currently over half of Americans pay no income tax.” (The document also suggests cutting IRS funding in half, so don’t sweat it too much.) This is an unusual harkening back to the politics of “makers” and “takers” that lost the GOP the White House in 2012.

There’s also a call to “prohibit debt ceiling increases absent a declaration of war.” So it’s a call to default on the federal debt, which isn’t good for the economy. Or—and this would be the more fun read—he’s saying that in order to get his vote on a necessary debt ceiling increase, he’s first going to need to see that declaration of war.

The document also includes a call to finish the border wall “and name it after President Donald Trump”—in what might be a delicate way to dangle the gold watch and hope Trump doesn’t run again. It calls for 12-year term limits for both members of Congress and “government bureaucrats”—a plan to further cap policymaking expertise and outsource it to the private sector. And Scott proposes sunsetting “all federal legislation” in five years, because “if a law is worth keeping, Congress can pass it again.”

Why did he release this again? It reads like an early jump on the field from a guy who’s thinking about running for president and wants to distinguish himself from “the Washington insiders” who “believe in the old idea that we should never tell voters what we plan to do,” as he writes about himself in his postscript. Washington insiders like, say, Mitch McConnell, who for the next couple of years will have to deal with ambitious senators in his conference consciously disobeying his strategies to say they stood up to the swamp.

Scott denied to Politico that he was using this agenda to set up a presidential run, instead explaining that “I’m a business guy and I believe in plans.” Oh, for sure.

But while Scott released this through his individual campaign, he’s not just any senator. He’s the chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, the Senate GOP’s campaign arm, and a member of Senate GOP leadership. He should not count on Democrats to make that distinction when they run ads against candidates Scott recruited, tying them to unpopular planks in his agenda.

If Republicans win back one or both chambers of Congress, the most consequential thing they’ll achieve for Republican voters will be the very act of having won: They’ll have shut the door on Democrats’ legislative ambitions for at least two years.

In this sense, McConnell’s strategy of not previewing an agenda is more honest, because the agenda is to deprive Democrats of the ability to do what they want and “hold the line for two years” until they have another bid at the presidency. Scott’s agenda isn’t a preview of what Republican congressional majorities would do after the midterms. It’s a preview of the Republican presidential primary.